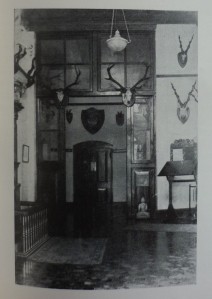

The Ajmer Bungalow is in the Civil Lines area of Ajmer City.

Built in 1908, it is a typical British colonial bungalow, standing in its own grounds. With a varied roof line which hints at cool, high-ceilinged interiors protected from the hot desert air by thick walls and deep, shaded verandas.... Home to the great grandchildren of Shankar Lal Capoor, who came to Ajmer from Agra over 150 years ago, the Ajmer Bungalow, from the outside, looks exactly as it did when it was built. The interiors have been brought up to date with modern bathrooms and air conditioning and are furnished with our own furniture, books and paintings. | The house is approached across a large front lawn, the scene of many merry gatherings of family and friends. The smaller, more private, tranquil garden at the back is a birdwatcher’s paradise or the quiet reader’s haven. Conveniently close to the bus stop and station, ten minutes drive from the Old Bazaar and major sights of interest.

---------

Peora Dak Bungalow, Almora ----------- |

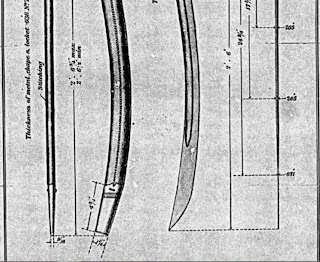

At the Wilkinson factory, manufacturing bayonets, swords and Indian Tulwars. 1916

https://gillww1.wordpress.com/tag/india/

gillww1

Research on the Gill family's service in the First World War

RHG visit to India – November 1914

1

The First World War broke out in August 1914 and many men in

Australia rushed to volunteer for the army that was speedily being

raised to fight in Europe. But Reg did not volunteer at first.

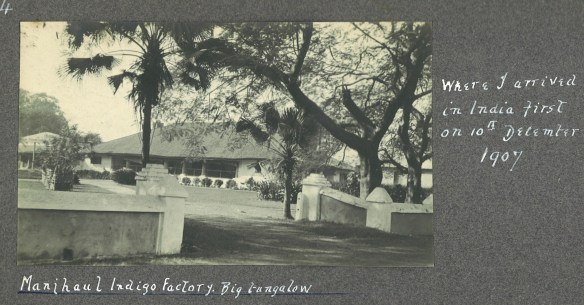

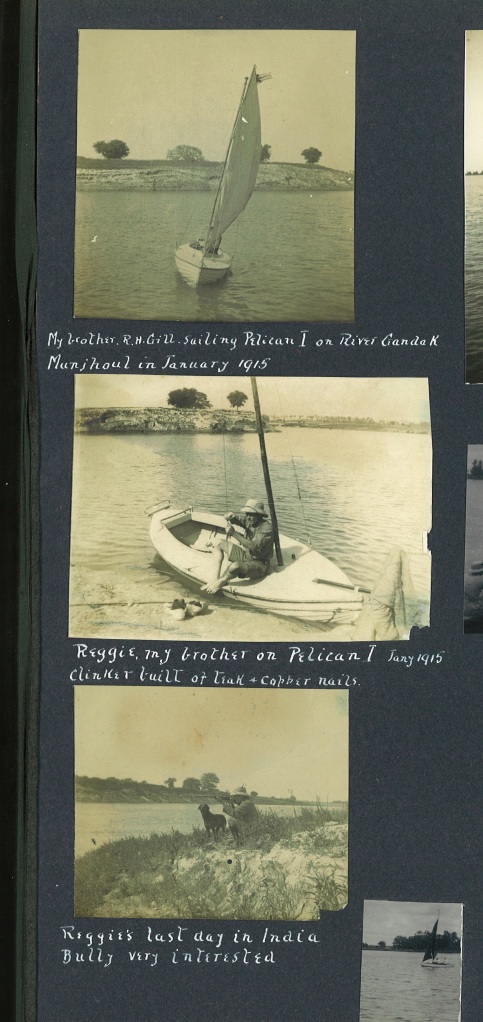

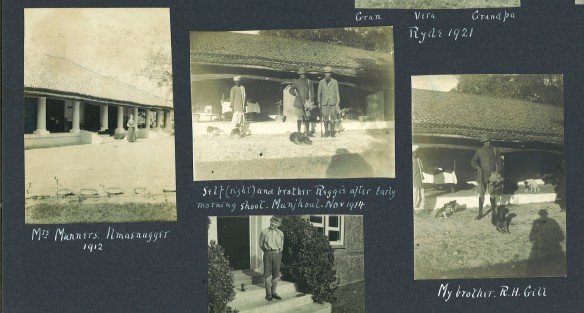

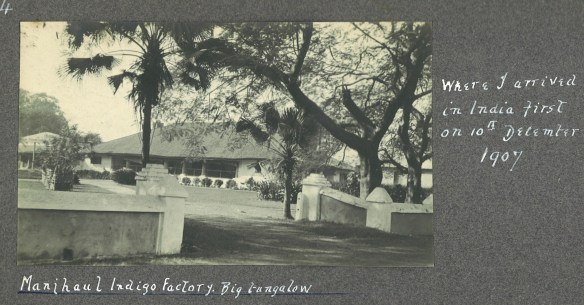

In late 1914 Reg visited his brother Theo (GTG) who was on the staff of an indigo plantation in India (Manjhaul, Bihar State). Reg is recorded in a local paper as visiting India for six months, returning in March 1915 (Daily News, 12 March 1915). Six months seems a long time to be away, especially if Reg had his own business or was working as an accountant or clerk for a company. It is interesting that Reg’s wife Laura does not seem to have gone with him. According to the same local paper, Laura had been on her own six month trip to the UK and Europe in 1912 ‘Mrs. Reginald Gill, of Fremantle, who is on a six months’ holiday In tho old country, leaves this month (says an English paper) on a tour of Holland, Switzerland, the Rhine, and Norway.’ (Daily News, 12 July 1912)

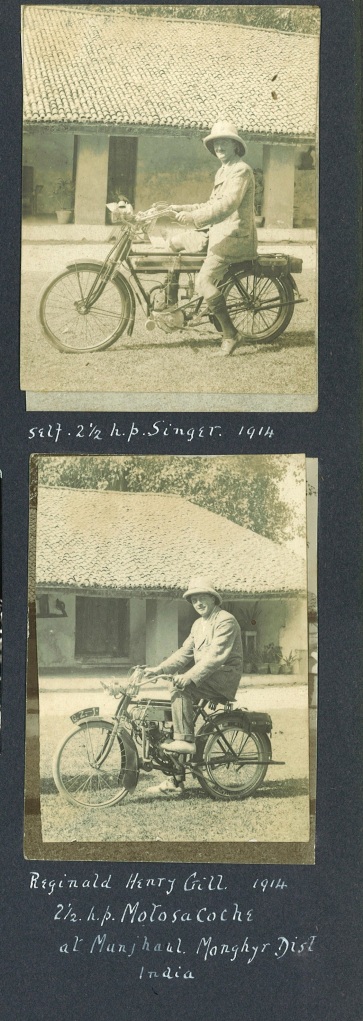

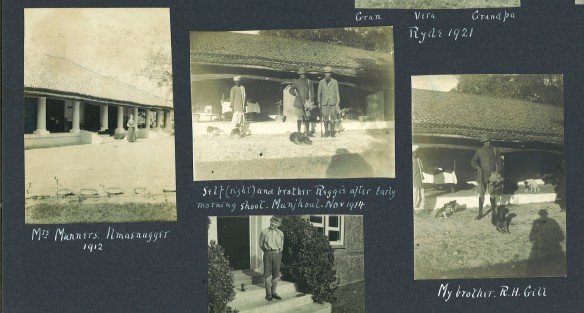

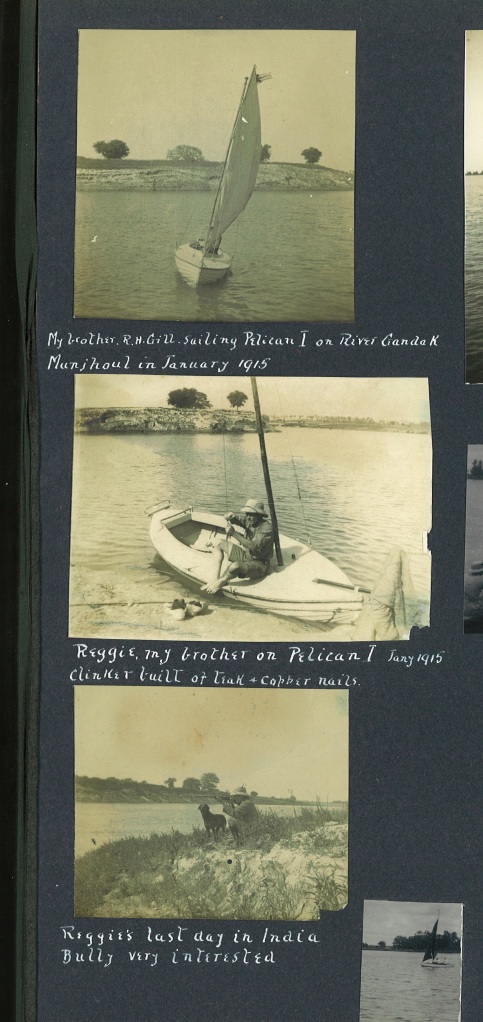

It is not known whether Reg spent all six months with Theo or just a part of this time. From the dates of the photos Reg was with Theo from at least November 1914 to January 1915 – click the following photos to enlarge:

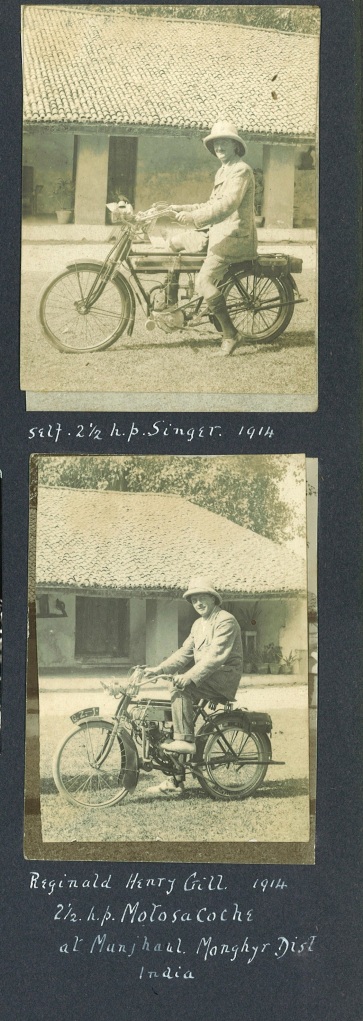

Theo is seen on a 2½ hp Singer motorcycle and Reggie is on a 2½ hp Motosacoche.

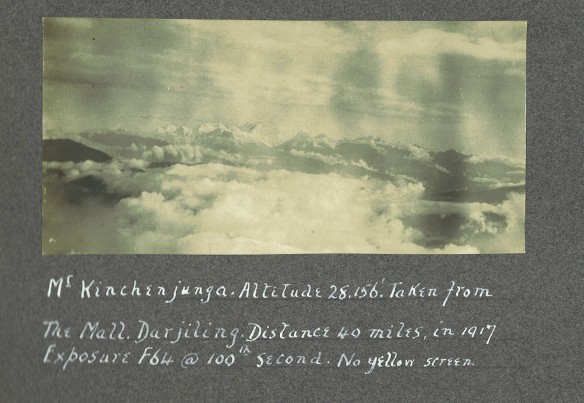

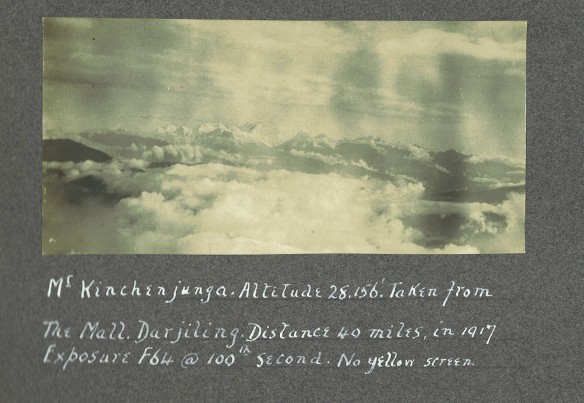

Reg’s letters to Theo from the Western Front nostalgically mention a trip they took with friends up to Darjeeling.

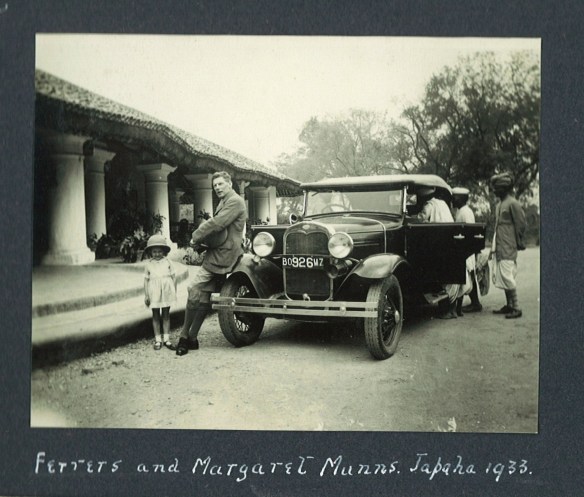

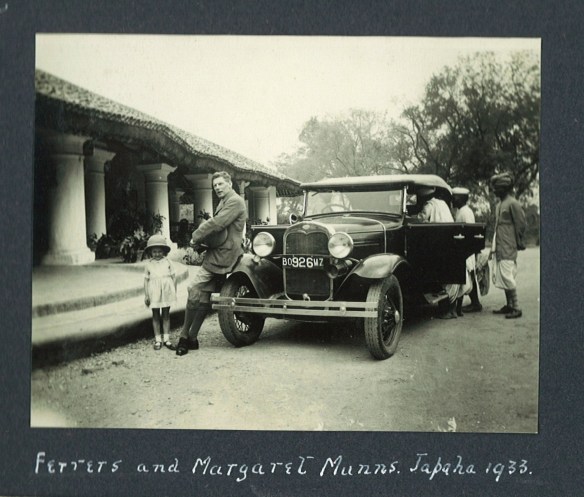

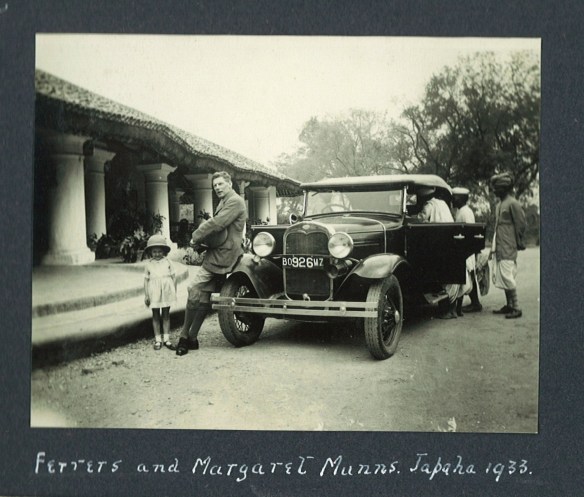

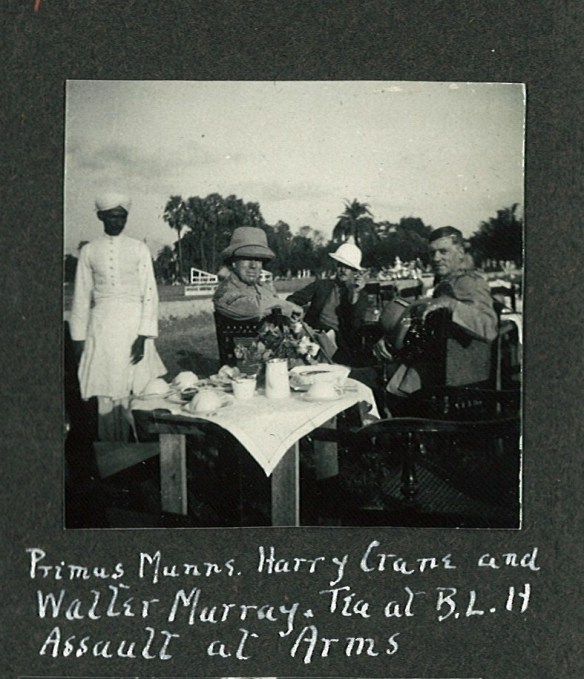

The letters also mention The “Munns” and the “Macs” and the “Finch tribe” – possibly Ferrers and Kathleen Munns and their daughters Margaret and Helen, Mr and Mrs E.G. Macpherson and E.J. Finch pictured in later years in Theo’s photo album.

E.J. Finch was a manager at the Indigo estate at Manjhaul in the state of Bihar where GTG worked.

In late 1914 Reg visited his brother Theo (GTG) who was on the staff of an indigo plantation in India (Manjhaul, Bihar State). Reg is recorded in a local paper as visiting India for six months, returning in March 1915 (Daily News, 12 March 1915). Six months seems a long time to be away, especially if Reg had his own business or was working as an accountant or clerk for a company. It is interesting that Reg’s wife Laura does not seem to have gone with him. According to the same local paper, Laura had been on her own six month trip to the UK and Europe in 1912 ‘Mrs. Reginald Gill, of Fremantle, who is on a six months’ holiday In tho old country, leaves this month (says an English paper) on a tour of Holland, Switzerland, the Rhine, and Norway.’ (Daily News, 12 July 1912)

It is not known whether Reg spent all six months with Theo or just a part of this time. From the dates of the photos Reg was with Theo from at least November 1914 to January 1915 – click the following photos to enlarge:

Theo is seen on a 2½ hp Singer motorcycle and Reggie is on a 2½ hp Motosacoche.

Reg’s letters to Theo from the Western Front nostalgically mention a trip they took with friends up to Darjeeling.

The letters also mention The “Munns” and the “Macs” and the “Finch tribe” – possibly Ferrers and Kathleen Munns and their daughters Margaret and Helen, Mr and Mrs E.G. Macpherson and E.J. Finch pictured in later years in Theo’s photo album.

E.J. Finch was a manager at the Indigo estate at Manjhaul in the state of Bihar where GTG worked.

“MUNJHOUL

One has to give but a cursory glance at

the 4,500 acres of land on the Munjhoul estate, in the district of

Monghyr, cultivated on behalf of the proprietor, to see that farming

operations have been conducted on thoroughly up-to-date principles,

chief among which are a systematic course of manuring and the draining

of superfluous water from the soil.

The whole estate comprises an area of

about fifteen square miles in extent, and the control of this huge

property is vested in Mr. F. H. Holloway, for whom Mr. E. J. Finch is

manager. About 4,500 acres are kept in hand, and Java indigo (700

acres), wheat, chillies, tobacco, and other, native crops are grown

successfully.

An indigo factory was built at Munjhoul,

on a bank of the little Gandak River, in or about the year 1836, and the

produce, manufactured under the old system of beating by the hand, may

be put down at an average of 9 seers to the acre. The only steam power

used on the premises is in connection with the processes of boiling and

the pumping of water for the vats. Tobacco, cured on racks, yields 8

maunds to the acre, and all crops are sold where grown, with the

exception of indigo, which is sent for disposal to Messrs. Begg, Dunlop

& Co., the agents in Calcutta.

The four out-stations are : Sisanni, seven

miles distant in an eastwardly direction from headquarters ; Bundwar,

four miles to the south ; Gurkpura, nine miles to the north ; and

Bissenpore, four miles to the west.

The buildings are substantially

constructed, and include five very nice bungalows, factory, carpentering

and other shops, sheds, and stores. Constant work upon the land is

found for sixty-five pairs of oxen, and about three hundred permanent

labourers are required for other duties.

Mr. Finch is assisted in the management by Messrs. P. F. Baddeley-Holloway and H. N. Philiffe.” extract from ‘BENGAL

AND ASSAM, BEHAR AND ORISSA, Their History, People, Commerce, and

Industrial Resources’, Compiled by SOMERSET PLAYNE, F.R.G.S. (1917)

RHG at sea 2 – with P&O

Image

Reggie’s service file in the archives of the Australian War

Memorial in Canberra record that had been ‘Officer Mercantile Marine’

with the P&O Company.

The

‘Mercantile Marine’ was the earlier name for the Merchant Navy – the

collective title for all the commercial shipping (i.e. non-military)

both the UK registered ships and their crews. During the First World

War, the loss of British commercial shipping to German U-boats was so

great (around 14,600 merchant seafarers lost their lives and 7,759,090

tons of ships were sunk) that King George V granted the title ‘Merchant Navy’ to the service in honour of their sacrifice. All British registered vessels fly the Red Ensign and have done so since 1674.

The

‘Mercantile Marine’ was the earlier name for the Merchant Navy – the

collective title for all the commercial shipping (i.e. non-military)

both the UK registered ships and their crews. During the First World

War, the loss of British commercial shipping to German U-boats was so

great (around 14,600 merchant seafarers lost their lives and 7,759,090

tons of ships were sunk) that King George V granted the title ‘Merchant Navy’ to the service in honour of their sacrifice. All British registered vessels fly the Red Ensign and have done so since 1674.

The P&O Company – The Peninsula and Orient Steamship Navigation Company – was probably the most famous of shipping lines in the Merchant Navy. It started in 1832 operating routes primarily between Britain and the Iberian Peninsula (i.e. Spain and Portugal) – using the name Peninsular Steam Navigation Company. The company flag colours are directly connected with the Peninsular flags: the white and blue represent the Portuguese flag at the time in 1837, in combination with the yellow and red the Spanish flag.

In 1837, the business won a contract from the Admiralty to deliver

mail to the Iberian Peninsula and in 1840 they acquired a contract to

deliver mail to Alexandria in Egypt. The present company, the Peninsular

and Oriental Steam Navigation Company, was incorporated in that year by

a Royal Charter. Mail contracts were the basis of P&O’s prosperity

until the Second World War, but the company also became a major

commercial shipping line and passenger liner operator. In 1914, it took

over the British India Steam Navigation Company (‘BI’), which

was then the largest British shipping line, owning 131 steamers. In

1918, it gained a controlling interest in the Orient Line,

its partner in the England- Australia mail route. Further acquisitions

followed and the fleet reached a peak of almost 500 ships in the

mid-1920s. In 1920, the company also established a bank, P&O Bank,

that it sold to Chartered Bank of India, Australia and

China (now Standard Chartered Bank) in 1927.

colours are directly connected with the Peninsular flags: the white and blue represent the Portuguese flag at the time in 1837, in combination with the yellow and red the Spanish flag.

In 1837, the business won a contract from the Admiralty to deliver

mail to the Iberian Peninsula and in 1840 they acquired a contract to

deliver mail to Alexandria in Egypt. The present company, the Peninsular

and Oriental Steam Navigation Company, was incorporated in that year by

a Royal Charter. Mail contracts were the basis of P&O’s prosperity

until the Second World War, but the company also became a major

commercial shipping line and passenger liner operator. In 1914, it took

over the British India Steam Navigation Company (‘BI’), which

was then the largest British shipping line, owning 131 steamers. In

1918, it gained a controlling interest in the Orient Line,

its partner in the England- Australia mail route. Further acquisitions

followed and the fleet reached a peak of almost 500 ships in the

mid-1920s. In 1920, the company also established a bank, P&O Bank,

that it sold to Chartered Bank of India, Australia and

China (now Standard Chartered Bank) in 1927.

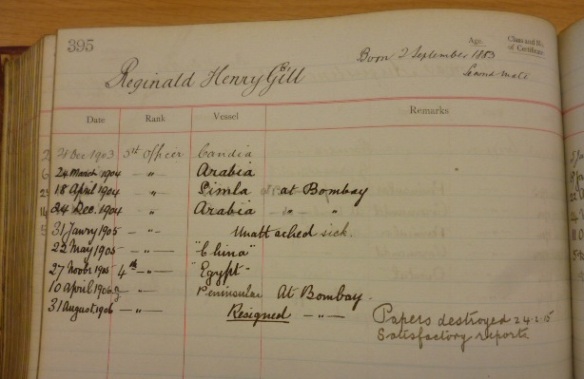

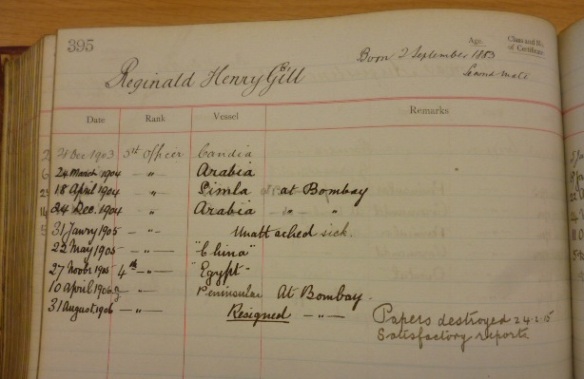

The National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, holds the company archives of P&O. In these archives, I unearthed Reggie’s employment record (I also discovered confirmation of his brother Theo’s employment as a clerk at the P&O head office in London):

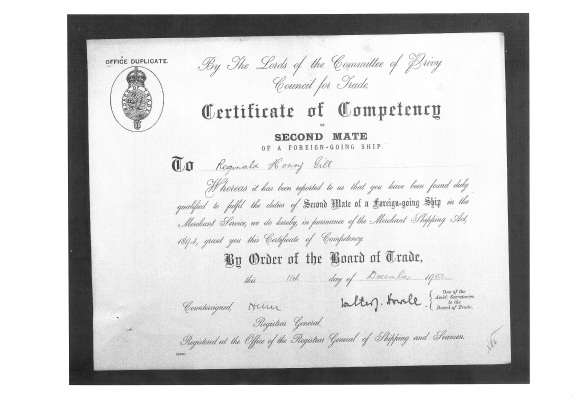

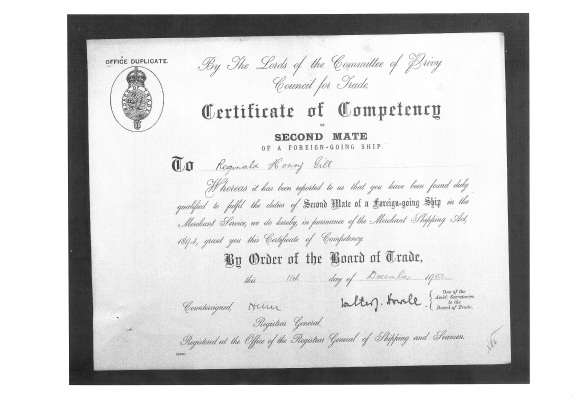

Reggie is recorded as ‘second mate’ just under his date of birth at the top of the page, which I assume means that he held a Second Mates Certificate of Competency, which I presume he obtained from his apprenticeship with Thomas Stephens & Son.

[09/09/14 – I have just received this copy of Reg’s Certificate of Competency as Second Mate, dated … 11 December 1903]

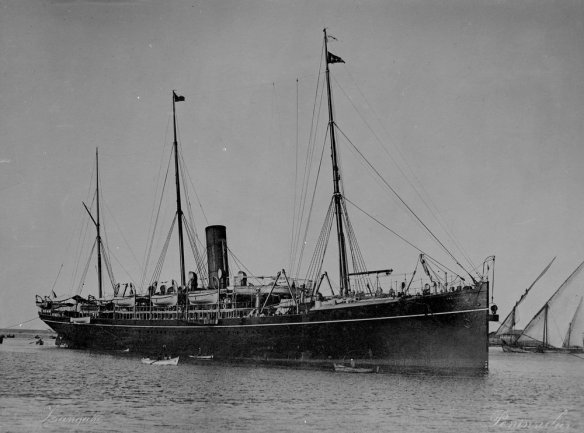

Reggie started at P&O as 5th Officer of the Candia on 28 December 1903.The Candia was a genral cargo liner, launched in 1896 and plying the route between the UK and Australia. It was sunk by a German U-boat in 1917.

Four months later Reggie transferred to the Arabia, on 24 March 1904.

Four months later Reggie transferred to the Arabia, on 24 March 1904.

The Arabia was a passenger liner, launched in 1898, in service on the route between the UK and India. The Arabia took Lord Curzon to India in 1898 to take up his his appointmentas Viceroy and in 1902 took a full load of passengers to the Delhi Durbar, who nicknamed her ‘RMS Grosvenor Square’. The Arabia was also sunk by a German U-boat during the First World War.

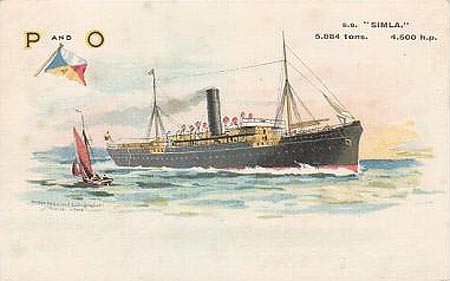

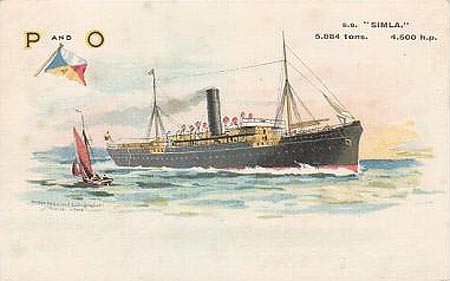

But less than a month after joining the Arabia, on 18 April 1904 Reggie transferred to the Simla, in Bombay, so I imagine he was only on the Arabia for the voyage out from England to India.

The Simla was a passenger/cargo liner which was adapted as a troopship, carrying Indian troops to the Boer War and later used in famine relief in India. It too was sunk by a German U-boat, in April 1916.

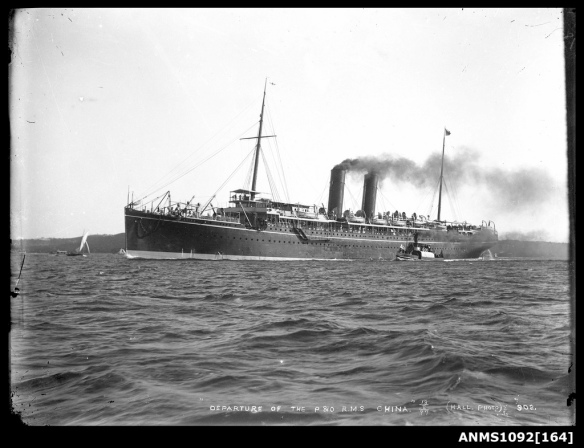

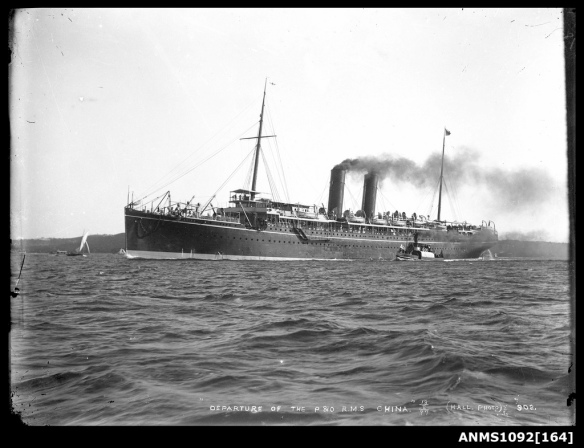

Reggie was back on the Arabia on Christmas Eve 1904 in Bombay, but again just for a single month. From 31 January to May 1905, Reggie was off sick and on 22 May he joined the China – one of five sister ships of the Arabia:

The China was on the UK/India and UK/Australia mail route and in 1902 broke the record from Fremantle to Colombo with a run of 8 days and 28 minutes. From the on-line archive of local newspapers in Australia I have discovered the first mention of Reggie in Fremantle, as Fifth Officer on board the RMS China which called very briefly in the port on 27 June 1905 en route to the Eastern States. (It seems a ship used the title “R.M.S.”, meaning “Royal Mail Ship” – ‘a designation which dates back to 1840, is the ship prefix used for seagoing vessels that carry mail under contract to the British Royal Mail. Any vessel designated as RMS has the right to both fly the pennant of the Royal Mail when sailing and to include the Royal Mail “crown” logo with any identifying device and/or design for the ship’):

Another newspaper records the China in meticulous detail in 1900 after a recent refit:

The P&O Company – The Peninsula and Orient Steamship Navigation Company – was probably the most famous of shipping lines in the Merchant Navy. It started in 1832 operating routes primarily between Britain and the Iberian Peninsula (i.e. Spain and Portugal) – using the name Peninsular Steam Navigation Company. The company flag

colours are directly connected with the Peninsular flags: the white and blue represent the Portuguese flag at the time in 1837, in combination with the yellow and red the Spanish flag.

In 1837, the business won a contract from the Admiralty to deliver

mail to the Iberian Peninsula and in 1840 they acquired a contract to

deliver mail to Alexandria in Egypt. The present company, the Peninsular

and Oriental Steam Navigation Company, was incorporated in that year by

a Royal Charter. Mail contracts were the basis of P&O’s prosperity

until the Second World War, but the company also became a major

commercial shipping line and passenger liner operator. In 1914, it took

over the British India Steam Navigation Company (‘BI’), which

was then the largest British shipping line, owning 131 steamers. In

1918, it gained a controlling interest in the Orient Line,

its partner in the England- Australia mail route. Further acquisitions

followed and the fleet reached a peak of almost 500 ships in the

mid-1920s. In 1920, the company also established a bank, P&O Bank,

that it sold to Chartered Bank of India, Australia and

China (now Standard Chartered Bank) in 1927.

colours are directly connected with the Peninsular flags: the white and blue represent the Portuguese flag at the time in 1837, in combination with the yellow and red the Spanish flag.

In 1837, the business won a contract from the Admiralty to deliver

mail to the Iberian Peninsula and in 1840 they acquired a contract to

deliver mail to Alexandria in Egypt. The present company, the Peninsular

and Oriental Steam Navigation Company, was incorporated in that year by

a Royal Charter. Mail contracts were the basis of P&O’s prosperity

until the Second World War, but the company also became a major

commercial shipping line and passenger liner operator. In 1914, it took

over the British India Steam Navigation Company (‘BI’), which

was then the largest British shipping line, owning 131 steamers. In

1918, it gained a controlling interest in the Orient Line,

its partner in the England- Australia mail route. Further acquisitions

followed and the fleet reached a peak of almost 500 ships in the

mid-1920s. In 1920, the company also established a bank, P&O Bank,

that it sold to Chartered Bank of India, Australia and

China (now Standard Chartered Bank) in 1927.The National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, holds the company archives of P&O. In these archives, I unearthed Reggie’s employment record (I also discovered confirmation of his brother Theo’s employment as a clerk at the P&O head office in London):

Reggie is recorded as ‘second mate’ just under his date of birth at the top of the page, which I assume means that he held a Second Mates Certificate of Competency, which I presume he obtained from his apprenticeship with Thomas Stephens & Son.

[09/09/14 – I have just received this copy of Reg’s Certificate of Competency as Second Mate, dated … 11 December 1903]

Reggie started at P&O as 5th Officer of the Candia on 28 December 1903.The Candia was a genral cargo liner, launched in 1896 and plying the route between the UK and Australia. It was sunk by a German U-boat in 1917.

The Arabia was a passenger liner, launched in 1898, in service on the route between the UK and India. The Arabia took Lord Curzon to India in 1898 to take up his his appointmentas Viceroy and in 1902 took a full load of passengers to the Delhi Durbar, who nicknamed her ‘RMS Grosvenor Square’. The Arabia was also sunk by a German U-boat during the First World War.

But less than a month after joining the Arabia, on 18 April 1904 Reggie transferred to the Simla, in Bombay, so I imagine he was only on the Arabia for the voyage out from England to India.

The Simla was a passenger/cargo liner which was adapted as a troopship, carrying Indian troops to the Boer War and later used in famine relief in India. It too was sunk by a German U-boat, in April 1916.

Reggie was back on the Arabia on Christmas Eve 1904 in Bombay, but again just for a single month. From 31 January to May 1905, Reggie was off sick and on 22 May he joined the China – one of five sister ships of the Arabia:

The China was on the UK/India and UK/Australia mail route and in 1902 broke the record from Fremantle to Colombo with a run of 8 days and 28 minutes. From the on-line archive of local newspapers in Australia I have discovered the first mention of Reggie in Fremantle, as Fifth Officer on board the RMS China which called very briefly in the port on 27 June 1905 en route to the Eastern States. (It seems a ship used the title “R.M.S.”, meaning “Royal Mail Ship” – ‘a designation which dates back to 1840, is the ship prefix used for seagoing vessels that carry mail under contract to the British Royal Mail. Any vessel designated as RMS has the right to both fly the pennant of the Royal Mail when sailing and to include the Royal Mail “crown” logo with any identifying device and/or design for the ship’):

“At 10.30 yesterday morning the P. and

O. Co.’s favourite liner China arrived at Fremantle from London and

ports, and berthed at the Quay. Since her last visit to Australia some

changes have taken place in the personnel of the officers of the ship.

Captain Lockyer is now in charge, and has with him the

following:-Chief, G. F. Caldwell; second, R. C. Warden; third, A.

Martell; supernumerary, J. McGregor; fourth, J. Plumpton.; fifth, R. H.

Gill; surgeon, E. Kennedy; chief engineer, W. C. Walker; purser, W.

Bervice. Captain Lockyer reports as follows on the trip:-“Left London on

the 26th May with 91 passengers and a general cargo. Fine weather

prevailed until Gibraltar, which was reached on 30th May, and it was

here that the first news was received of the battle between the two

opposing fleets in the Far East. From Gibraltar to Marseilles (lst

June) fine weather ,with light winds, was experienced. At 10 a.m. on the

2nd June the China left Marseilles, having embarked 64 passengers.

Port Said was reached on 6th inst. and upon the arrival of the mail

packet Osiris, at 6 a.m. the following day. passengers and mails

from Europe were transferred to the China. A rapid transit through the

Canal was effected, and the China left Suez shortly after midnight,

arriving in Aden on Sunday, 11th June, at 8 a.m. Here the China

transferred 30 of her passengers, with the mails for India. to the P.

and O. steamer Arcadia. The voyage down the Red sea was pleasant, with a

strong N. wind. Leaving Aden at 1 p.m. on the 11th inst.. the

China commenced her run down to Colombo. This was a pleasant surprise,

for a light monsoon, with fine, clear weather, was experienced for

the whole distance. Arriving at Colombo on the 17th June, the China

connected with the Chusan, transferring passengers and mails for China

and Japanese ports. Left Colombo shortly after midnight, and in a few

hours a heavy swell from the S.E. was experienced. Dull weather, with

heavy rain squalls, accompanied by a moderate sea, now set in until the

23rd. when the weather cleared considerably, although the S.E. wind and

swell continued all the way to Fremantle.” (source: The West Australian 28 June 1905)

The China brought a few passengers for Fremantle, as well as about

200 tons of general cargo. She embarked a large number of voyagers, and

resumed her voyage to the Eastern States during the afternoon.”

Another newspaper records the China in meticulous detail in 1900 after a recent refit:

“R.M.S. CHINA.

The reappearance in the colonies of the R.M.S.China is an interesting event, and visitors to PortMelbourne to-day will have an opportunity of again viewing this noted liner. The disaster which she met with on the rocks at Perim, her narrow escape, from total destruction, and her subsequent flotation and rehabilitation are matters of history. She was almost entirely re-built, and advantage was taken of the opportunity to make several improvements to the vessel on her original construction. The China is 514ft. long, 54ft.broad, and 37ft. deep. Her engines are of the new four cylinder triple and expansion type, giving 11,000 indicated horse-power. She can steam 17½ knots with ease. Her gross tonnage is 7,899 tons,and she can accommodate 313 first and 152 second saloon passengers, in addition to 187 European officers and crew, and 179 natives. The China has many improvements, one of the most important being that the cabins of the commander and the six other officers are all located together on the bridge deck. Above them rises the upper bridge,from which the vessel is steered. This bridge is 55 ft. above the water line, and being situated well forward enables a capital look-out to he kept. The first-class dining saloon is amidships, a little for-ward of the engines, and measures 76 by 52 feet,having a height to the gable roof of the music saloon above of about 36ft. It is capable, of seat-ing 242 passengers. The saloon and all other parts of the ship are supplied with a complete electric light installation, and, as is the case in the second saloon, with punkahs for use in the tropics. The second-class saloon is situated aft. The companion and smokingroom arc decorated tastefully, The dining saloon provides seating accommodation for153, and is furnished in mahogany, with a handsome wallpaper picked out with a rich design in pink and gilt. Cabins are fitted with all the latest interior comforts. A feature of the ship is the large number of bathrooms, 34 in all, which are located on all the decks and provided with hot and cold water. The China is under the command of Captain T. S. Angus, an old and popular servant of the company, who is assisted in the navigation by a staff of six officers. Passengers have ample room for exorcise, as the promenade or hurricane deck is 267ft. long, or about a quarter of a mile round, while the second saloon deck is most spacious. The China is dividcd into ten water-tight bulkheads, has a cellular double bot-tom, and can, if necessary, carry from 800 to 900tons of water ballast. She is altogether, a magnificent specimen of her kind.” (from The Argus (Melbourne) 9 July 1900)

The reappearance in the colonies of the R.M.S.China is an interesting event, and visitors to PortMelbourne to-day will have an opportunity of again viewing this noted liner. The disaster which she met with on the rocks at Perim, her narrow escape, from total destruction, and her subsequent flotation and rehabilitation are matters of history. She was almost entirely re-built, and advantage was taken of the opportunity to make several improvements to the vessel on her original construction. The China is 514ft. long, 54ft.broad, and 37ft. deep. Her engines are of the new four cylinder triple and expansion type, giving 11,000 indicated horse-power. She can steam 17½ knots with ease. Her gross tonnage is 7,899 tons,and she can accommodate 313 first and 152 second saloon passengers, in addition to 187 European officers and crew, and 179 natives. The China has many improvements, one of the most important being that the cabins of the commander and the six other officers are all located together on the bridge deck. Above them rises the upper bridge,from which the vessel is steered. This bridge is 55 ft. above the water line, and being situated well forward enables a capital look-out to he kept. The first-class dining saloon is amidships, a little for-ward of the engines, and measures 76 by 52 feet,having a height to the gable roof of the music saloon above of about 36ft. It is capable, of seat-ing 242 passengers. The saloon and all other parts of the ship are supplied with a complete electric light installation, and, as is the case in the second saloon, with punkahs for use in the tropics. The second-class saloon is situated aft. The companion and smokingroom arc decorated tastefully, The dining saloon provides seating accommodation for153, and is furnished in mahogany, with a handsome wallpaper picked out with a rich design in pink and gilt. Cabins are fitted with all the latest interior comforts. A feature of the ship is the large number of bathrooms, 34 in all, which are located on all the decks and provided with hot and cold water. The China is under the command of Captain T. S. Angus, an old and popular servant of the company, who is assisted in the navigation by a staff of six officers. Passengers have ample room for exorcise, as the promenade or hurricane deck is 267ft. long, or about a quarter of a mile round, while the second saloon deck is most spacious. The China is dividcd into ten water-tight bulkheads, has a cellular double bot-tom, and can, if necessary, carry from 800 to 900tons of water ballast. She is altogether, a magnificent specimen of her kind.” (from The Argus (Melbourne) 9 July 1900)

Reggie was promoted to 4th Officer on what looks like 27 November 1905, on the Egypt – the third of the five sister ships including the Arabia and the China:

And five months later, on 10 April 1906, Reggie transferred to the Peninsular at Bombay.

The Peninsular

was a slightly older passenger liner, having been launched in 1888. It

was originally in service with P&O on the route between the UK out

to India and the the Far East, but in

1904 she was refitted and modernised, together with several others of

P&O’s older ships, and put on the Aden/Bombay shuttle.

The employment record

states that Reggie resigned from P&O service in Bombay on 31 August

1906. It is not known why he resigned and what his plans were, but it

seems he arrived in Fremantle the following month.

The last record on file is the note “Papers destroyed 24 – 2- 15 Satisfactory reports”.

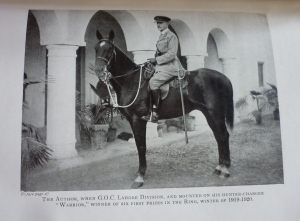

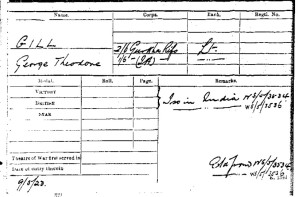

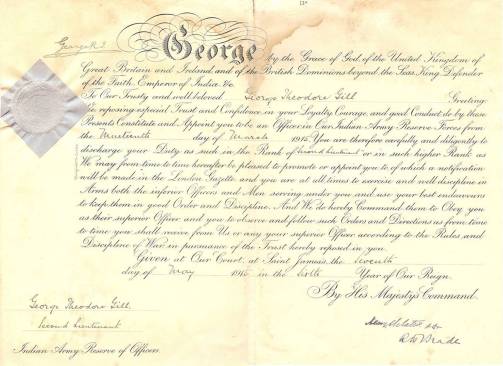

GTG – after the war with the Bihar Light Horse

It seems GTG remained on the staff at the School of Instruction for Young Officers at Sabathu and Ambala until 1919.

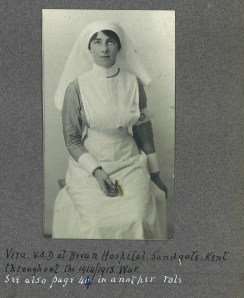

GTG’s service record is

unclear when he ceased his role as instructor at the school but it

seems from the photo album that he returned to civilian life quite soon

after the war. He was married on 30 December 1918 at St.Thomas’s

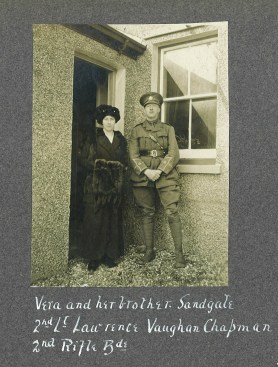

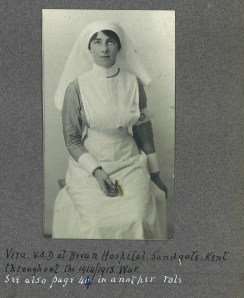

Cathedral, Bombay to Annie Vera Chapman (known as ‘Vera’). Vera served

in the war as a V.A.D. nurse at Bevan Hospital, Sandgate, Kent so how they met each other is unclear.

GTG’s service record is

unclear when he ceased his role as instructor at the school but it

seems from the photo album that he returned to civilian life quite soon

after the war. He was married on 30 December 1918 at St.Thomas’s

Cathedral, Bombay to Annie Vera Chapman (known as ‘Vera’). Vera served

in the war as a V.A.D. nurse at Bevan Hospital, Sandgate, Kent so how they met each other is unclear.

There is a photo in GTG’s album of Vera with her brother Lawrence Vaughan Chapman who was a Lieutenant in the 2nd Rifle Brigade and was killed in Flanders on 25 September 1915.

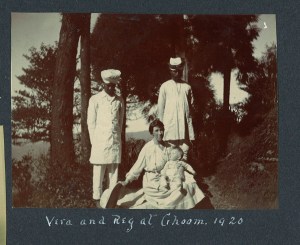

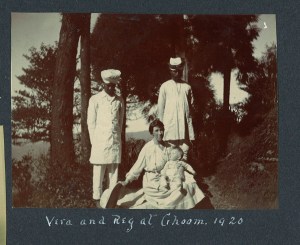

From 1919 GTG worked at the Russelpur indigo plantation and factory in North Bihar (I believe it is now called Rasulpur). And a year later, on 15th December 1919, GTG and Vera’s first child, Vaughan Reginald Gill (known as Reggie after his uncle RHG), was born.

From 1919 GTG worked at the Russelpur indigo plantation and factory in North Bihar (I believe it is now called Rasulpur). And a year later, on 15th December 1919, GTG and Vera’s first child, Vaughan Reginald Gill (known as Reggie after his uncle RHG), was born.

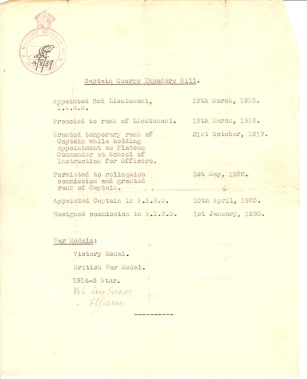

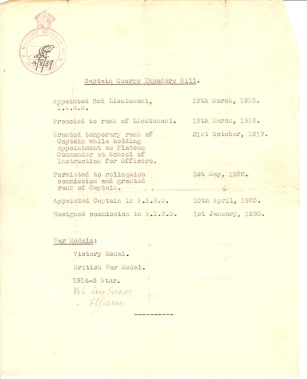

The photo album shows a long leave in England in 1921 where their second son David Lawrence George Gill (Dave) was born on 2nd August 1921, and then back to Russelpur. I assume GTG remained in the Indian Army Reserve of Officers (I.A.R.O.) until 1922 when his service record states that he was “Permitted to relinquish commission and granted rank of Captain – 1st May, 1922”. However it seems he was back in the I.A.R.O. in 1923 because the next entry in the service record states “Appointed Captain in I.A.R.O. – 10th April 1923”. I wonder why?

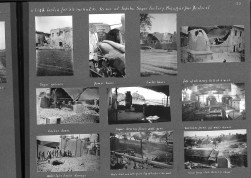

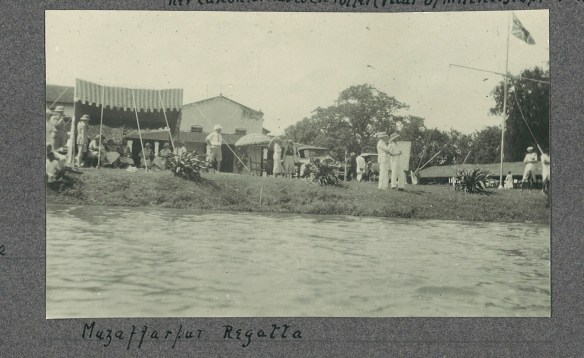

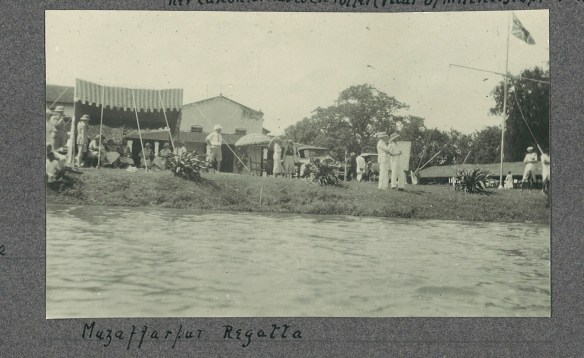

By this time it seems that GTG and family had moved to the Japaha sugar factory in Muzaffarpur District, Bihar,

which GTG describes was “HQ district of same name in province of Bihar

and Orissa, known as Tirhut, also called the garden of India”.

By this time it seems that GTG and family had moved to the Japaha sugar factory in Muzaffarpur District, Bihar,

which GTG describes was “HQ district of same name in province of Bihar

and Orissa, known as Tirhut, also called the garden of India”.

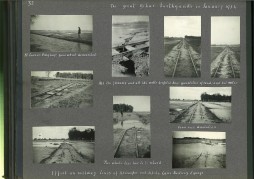

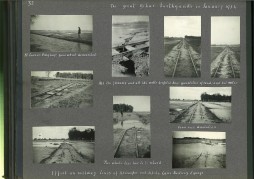

It was at Japaha that GTG and Vera’s third child Rosemary Theodora Mitchell Gill (Rosie) was born on 11th January 1924. There was a serious earthquake in Bihar in 1934, the devastating effects of which GTG captured by photograph in great detail.

1934 Bihar Earthquake (click photos to enlarge):

The

last entry in GTG’s service record states “Resigned commission in

A.I.R.O. – 1st January, 1930”. There are then a number of photos of

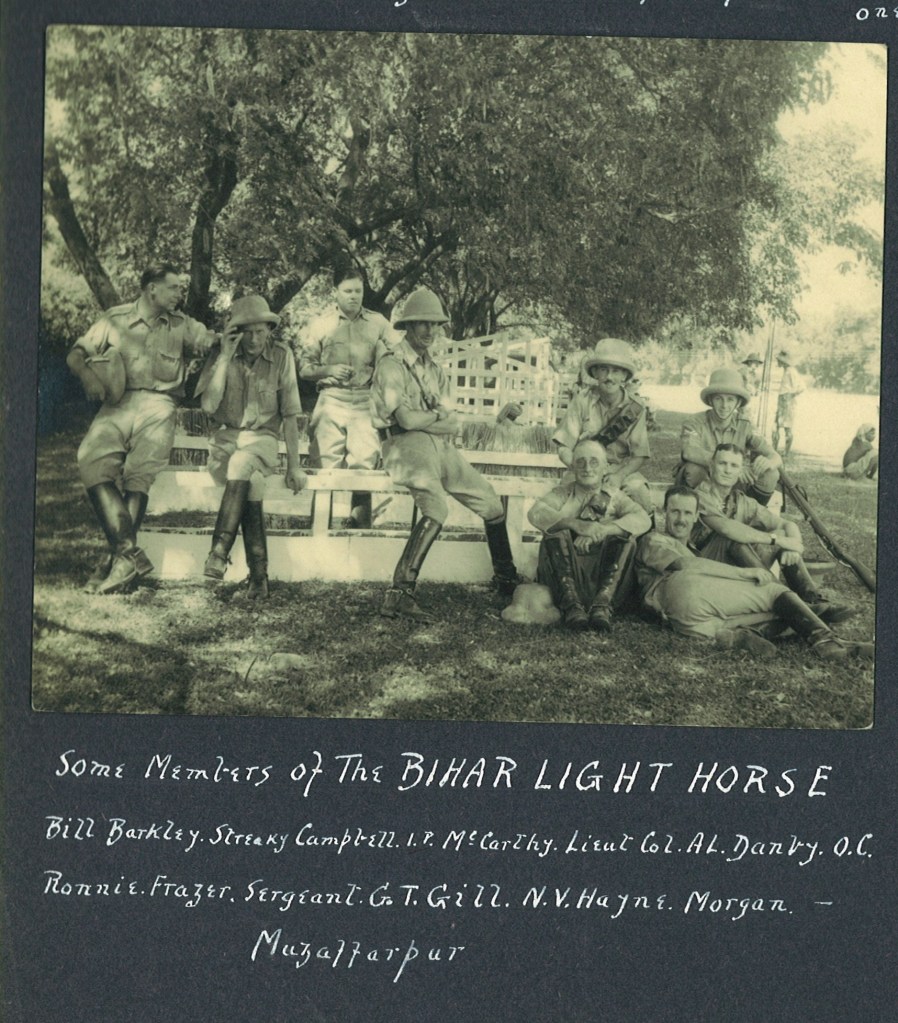

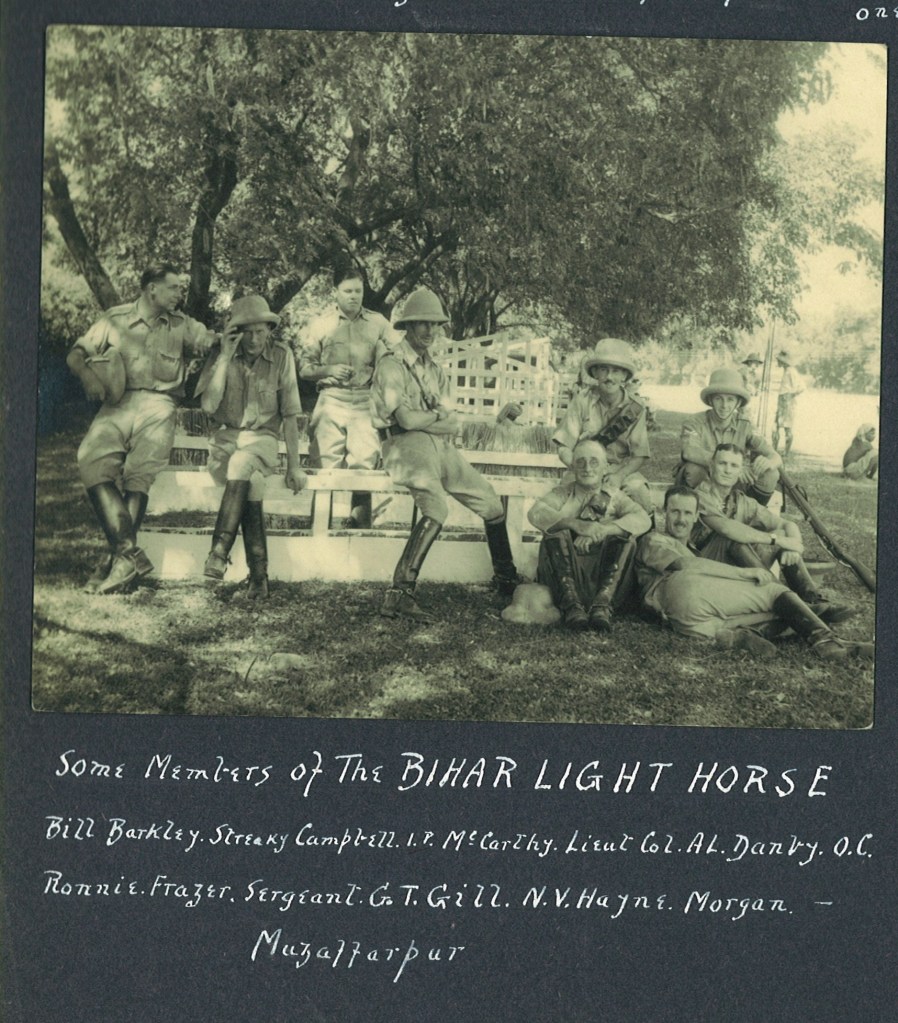

GTG from 1930 onwards in the Bihar Light Horse (BLH) based at Muzaffarpur.

The

last entry in GTG’s service record states “Resigned commission in

A.I.R.O. – 1st January, 1930”. There are then a number of photos of

GTG from 1930 onwards in the Bihar Light Horse (BLH) based at Muzaffarpur.

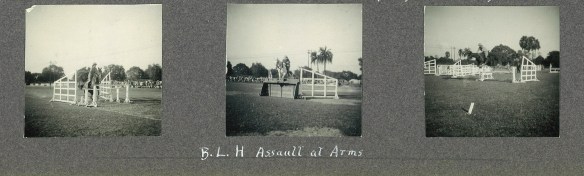

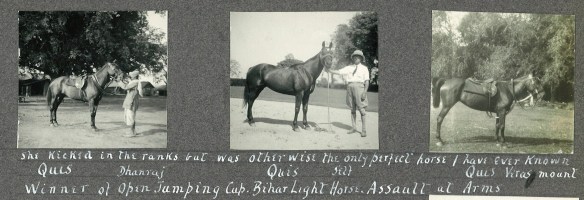

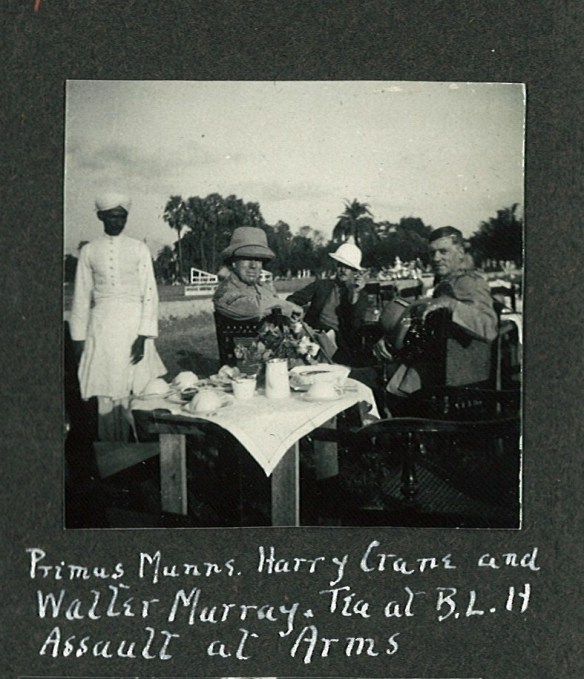

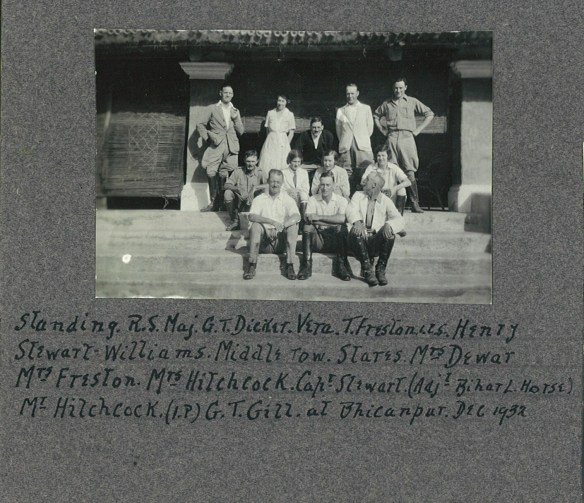

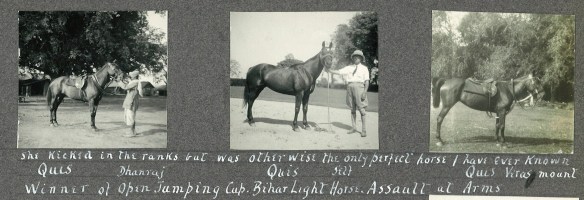

It seems GTG was given the rank of sergeant in the BLH. The BLH was part of the Auxiliary Force (India) and was a volunteer, part-time unit. I understand that it was quite popular to join such a ‘territorial’ unit, which were social hubs for British society in India, and due to the popularity it was common for former officers to join as other ranks. From the photos it certainly seems very sociable.

It seems that Ferrers Munns, who was a good friend of GTG, wrote a short booklet entitled “In Memory of the Bihar Light Horse” to commemorate the unveiling of a plaque to the BLH at Sandhurst in 1958. It is from this booklet that the various information on the BLH on the internet is taken.

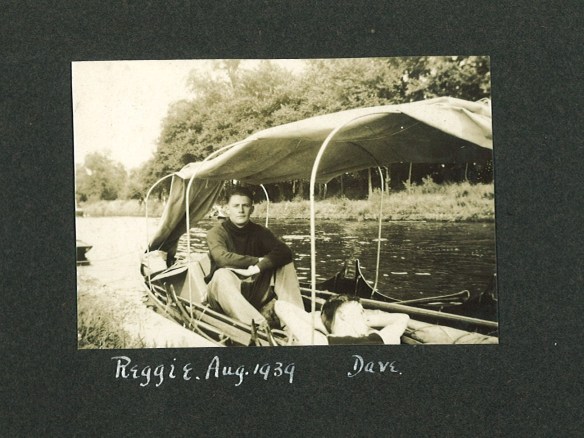

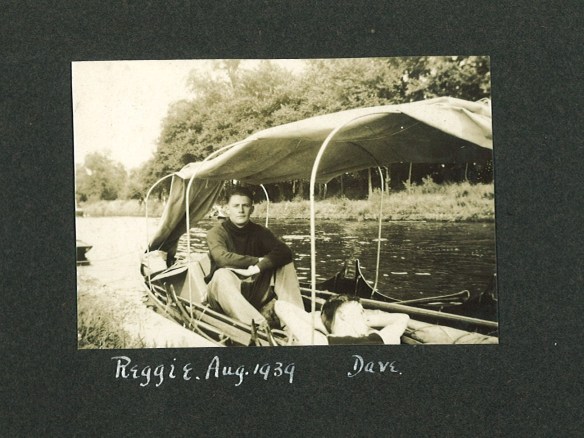

With war in Europe looming, GTG returned to the UK in 1939, living at Sunbury-on-Thames. I believe that during WWII he served as an officer in the Home Guard but unfortunately his photo album stops in the late 1930s. All three of GTG’s children Reggie, Dave and Rosie served in WWII. Reggie joined the Fleet Air Arm and trained as a pilot at NAS Brunswick in the USA. David joined the RAF and trained as a pilot in South Africa and Rosemary joined the W.R.N.S., stationed in London, Brighton and Edinburgh. And Vera served in the WVS in Sunbury – so the whole family was in uniform.

Tragically, Reggie died in a mid-air collision whilst on a training flight in a F4U-1 Corsair over Lake Sebago, Maine on 16 May 1944. It seems the two planes were discovered a few years ago submerged in the lake and there were plans to try to salvage the planes, but this was blocked in 2004 by legal action the State of Maine and the MOD.

GTG’s service record is

unclear when he ceased his role as instructor at the school but it

seems from the photo album that he returned to civilian life quite soon

after the war. He was married on 30 December 1918 at St.Thomas’s

Cathedral, Bombay to Annie Vera Chapman (known as ‘Vera’). Vera served

in the war as a V.A.D. nurse at Bevan Hospital, Sandgate, Kent so how they met each other is unclear.

GTG’s service record is

unclear when he ceased his role as instructor at the school but it

seems from the photo album that he returned to civilian life quite soon

after the war. He was married on 30 December 1918 at St.Thomas’s

Cathedral, Bombay to Annie Vera Chapman (known as ‘Vera’). Vera served

in the war as a V.A.D. nurse at Bevan Hospital, Sandgate, Kent so how they met each other is unclear.There is a photo in GTG’s album of Vera with her brother Lawrence Vaughan Chapman who was a Lieutenant in the 2nd Rifle Brigade and was killed in Flanders on 25 September 1915.

From 1919 GTG worked at the Russelpur indigo plantation and factory in North Bihar (I believe it is now called Rasulpur). And a year later, on 15th December 1919, GTG and Vera’s first child, Vaughan Reginald Gill (known as Reggie after his uncle RHG), was born.

From 1919 GTG worked at the Russelpur indigo plantation and factory in North Bihar (I believe it is now called Rasulpur). And a year later, on 15th December 1919, GTG and Vera’s first child, Vaughan Reginald Gill (known as Reggie after his uncle RHG), was born.The photo album shows a long leave in England in 1921 where their second son David Lawrence George Gill (Dave) was born on 2nd August 1921, and then back to Russelpur. I assume GTG remained in the Indian Army Reserve of Officers (I.A.R.O.) until 1922 when his service record states that he was “Permitted to relinquish commission and granted rank of Captain – 1st May, 1922”. However it seems he was back in the I.A.R.O. in 1923 because the next entry in the service record states “Appointed Captain in I.A.R.O. – 10th April 1923”. I wonder why?

By this time it seems that GTG and family had moved to the Japaha sugar factory in Muzaffarpur District, Bihar,

which GTG describes was “HQ district of same name in province of Bihar

and Orissa, known as Tirhut, also called the garden of India”.

By this time it seems that GTG and family had moved to the Japaha sugar factory in Muzaffarpur District, Bihar,

which GTG describes was “HQ district of same name in province of Bihar

and Orissa, known as Tirhut, also called the garden of India”.

It was at Japaha that GTG and Vera’s third child Rosemary Theodora Mitchell Gill (Rosie) was born on 11th January 1924. There was a serious earthquake in Bihar in 1934, the devastating effects of which GTG captured by photograph in great detail.

1934 Bihar Earthquake (click photos to enlarge):

The

last entry in GTG’s service record states “Resigned commission in

A.I.R.O. – 1st January, 1930”. There are then a number of photos of

GTG from 1930 onwards in the Bihar Light Horse (BLH) based at Muzaffarpur.

The

last entry in GTG’s service record states “Resigned commission in

A.I.R.O. – 1st January, 1930”. There are then a number of photos of

GTG from 1930 onwards in the Bihar Light Horse (BLH) based at Muzaffarpur.It seems GTG was given the rank of sergeant in the BLH. The BLH was part of the Auxiliary Force (India) and was a volunteer, part-time unit. I understand that it was quite popular to join such a ‘territorial’ unit, which were social hubs for British society in India, and due to the popularity it was common for former officers to join as other ranks. From the photos it certainly seems very sociable.

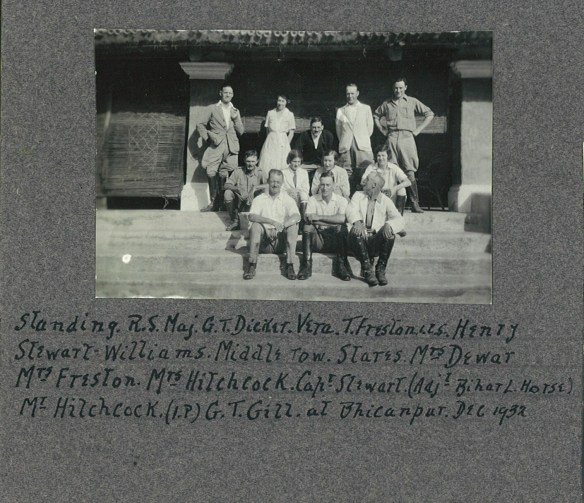

Some members of the Bihar Light Horse, Muzaffarpur

L to R: Bill Barkley, Streaky Campbell (I.P.), McCarthy, Lt. Col. A.L. Danby O.C

On R – back: Ronnie, Frazer; front L to R: Sgt. G.T.Gill, N.V. Hayne, Morgan

L to R: Bill Barkley, Streaky Campbell (I.P.), McCarthy, Lt. Col. A.L. Danby O.C

On R – back: Ronnie, Frazer; front L to R: Sgt. G.T.Gill, N.V. Hayne, Morgan

It seems that Ferrers Munns, who was a good friend of GTG, wrote a short booklet entitled “In Memory of the Bihar Light Horse” to commemorate the unveiling of a plaque to the BLH at Sandhurst in 1958. It is from this booklet that the various information on the BLH on the internet is taken.

With war in Europe looming, GTG returned to the UK in 1939, living at Sunbury-on-Thames. I believe that during WWII he served as an officer in the Home Guard but unfortunately his photo album stops in the late 1930s. All three of GTG’s children Reggie, Dave and Rosie served in WWII. Reggie joined the Fleet Air Arm and trained as a pilot at NAS Brunswick in the USA. David joined the RAF and trained as a pilot in South Africa and Rosemary joined the W.R.N.S., stationed in London, Brighton and Edinburgh. And Vera served in the WVS in Sunbury – so the whole family was in uniform.

Tragically, Reggie died in a mid-air collision whilst on a training flight in a F4U-1 Corsair over Lake Sebago, Maine on 16 May 1944. It seems the two planes were discovered a few years ago submerged in the lake and there were plans to try to salvage the planes, but this was blocked in 2004 by legal action the State of Maine and the MOD.

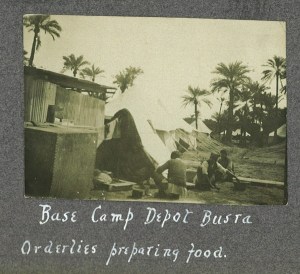

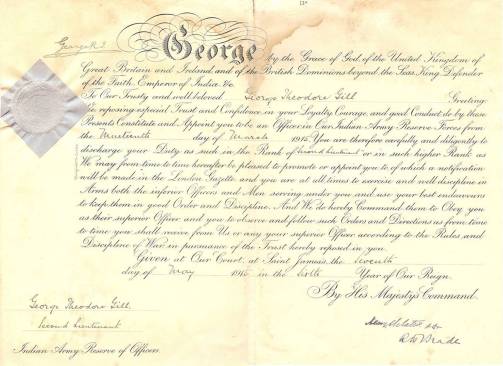

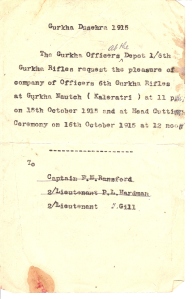

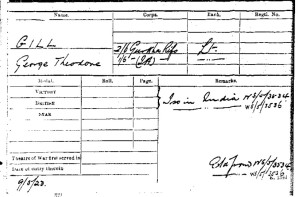

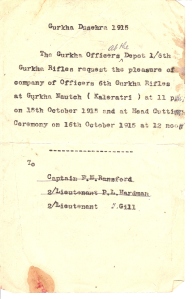

2/6th Gurkha Rifles in Mesopotamia 1916

In March 1916 GTG arrived by ship in Mesopotamia (now Iraq) serving with the 2/6th Gurkha Rifles. 2/6GR joined the 15th Indian Division which was formed in Mesopotamia in 1916 as part of the MEF – Mesopotamia Expeditionary Force. A brief explanation of the Mesopotamia campaign can be found here: Mesopotamia campaign – The National Archives

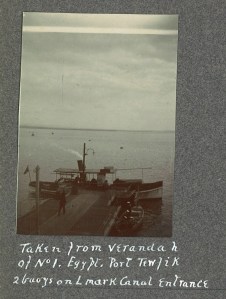

In March 1916 GTG arrived by ship in Mesopotamia (now Iraq) serving with the 2/6th Gurkha Rifles. 2/6GR joined the 15th Indian Division which was formed in Mesopotamia in 1916 as part of the MEF – Mesopotamia Expeditionary Force. A brief explanation of the Mesopotamia campaign can be found here: Mesopotamia campaign – The National ArchivesThe Battalion War Diary for 2/6GR in the first few months in Mesopotamia (transcription: War Diary 2-6GR March 1916 – May 1916) records their marching from camp to camp up the Euphrates river from Basra to Nasiriyah, constantly working on maintaining the flood defences in this low-lying waterlogged area. It seems disease was a constant threat and they record an outbreak of cholera.

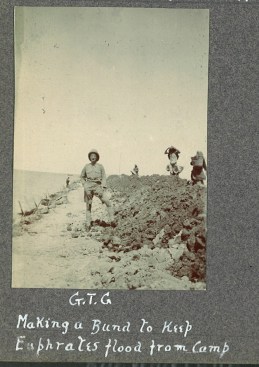

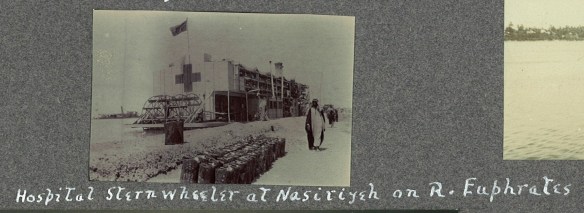

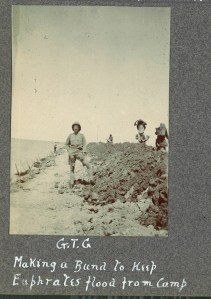

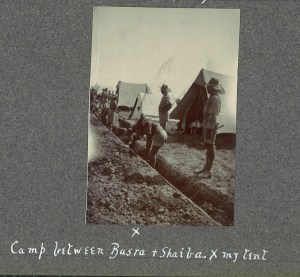

GTG took a number of photographs during this campaign. He records some of the key preoccupations from the War Diary – the endless bund construction and maintenance work (‘bund’ is the Anglo-Indian name for a river embankment or flood defenses, like ‘levee’) and the hospitals! It is not known if he made use of these but it seems many did. GTG also seems to have been very interested in the various ships and boats he saw, carefully noting their names and the companies that owned them, probably because of his initial career with P&O.

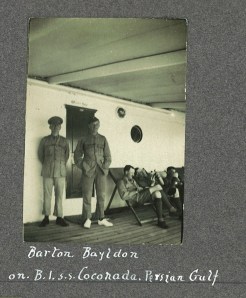

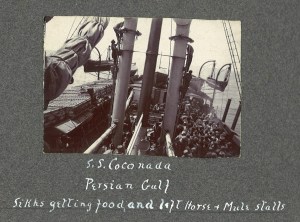

GTG arrived on the SS.Coconada. The Battalion War Diary records him arriving a bit later than the main battalion, on with 3 other B.O.s (British Officers – Captain Harte, Lieut. Barton and Lieut. Marley) and 208 other ranks from Suez. Lieut. Barton is recorded elsewhere (see below) as serving with 1/6 GR form 9.9.15 who I believe were still in Gallipoli but moved to Suez to assist guarding the canal in December 1915. If GTG was with Barton, on board in the Persian Gulf and then on arrival from Suez in Basra in March 1916, I assume GTG must have also served with 1/6GR at Gallipoli from September to December 1915.

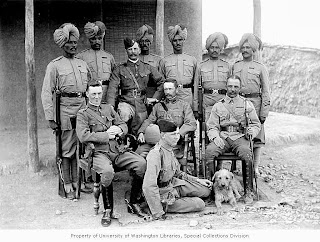

This

photo shows a Sikh regiment on board the SS Coconada in the Persian

Gulf. The horses and mules are in boxes on the port side of the ship

and the men are collecting food on the starboard.

This

photo shows a Sikh regiment on board the SS Coconada in the Persian

Gulf. The horses and mules are in boxes on the port side of the ship

and the men are collecting food on the starboard. Major

R. Maurice Searle Barton, T.D., “born in Frampton, Gloucestershire

4.8.1892; Second Lieutenant Indian Army Reserve of Officers, 18.12.1914;

attached 1st Battalion 6th Gurkha Rifles, 9.9.1915; Lieutenant

18.12.1915; served in Egypt and Mesopotamia during the Great War;

commanded “C” Company 2nd Battalion 6th Gurkha Rifles at Ramadi,

September 1917; Captain 18.12.1918; served with 1st Battalion 5th Gurkha

Rifles, 1918-1919; attached 2nd Battalion 11th Gurkha Rifles 1920;

retired 20.11.1922; Assistant Commandant, Mewar Bhil Corps and Assistant

Political Superintendent, Hilly Tracts, Mewar, 6.7.1926; re-engaged as

Staff Captain Royal Artillery (T.A.) for the Second War, 16.6.1939;

posted to Mountain Artillery Training Centre, Amballa, India; retired

Honorary Major, 2.11.1947″ (taken from http://www.abebooks.co.uk/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=6459279443&searchurl=an%3Dgurkhas)

Major

R. Maurice Searle Barton, T.D., “born in Frampton, Gloucestershire

4.8.1892; Second Lieutenant Indian Army Reserve of Officers, 18.12.1914;

attached 1st Battalion 6th Gurkha Rifles, 9.9.1915; Lieutenant

18.12.1915; served in Egypt and Mesopotamia during the Great War;

commanded “C” Company 2nd Battalion 6th Gurkha Rifles at Ramadi,

September 1917; Captain 18.12.1918; served with 1st Battalion 5th Gurkha

Rifles, 1918-1919; attached 2nd Battalion 11th Gurkha Rifles 1920;

retired 20.11.1922; Assistant Commandant, Mewar Bhil Corps and Assistant

Political Superintendent, Hilly Tracts, Mewar, 6.7.1926; re-engaged as

Staff Captain Royal Artillery (T.A.) for the Second War, 16.6.1939;

posted to Mountain Artillery Training Centre, Amballa, India; retired

Honorary Major, 2.11.1947″ (taken from http://www.abebooks.co.uk/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=6459279443&searchurl=an%3Dgurkhas)

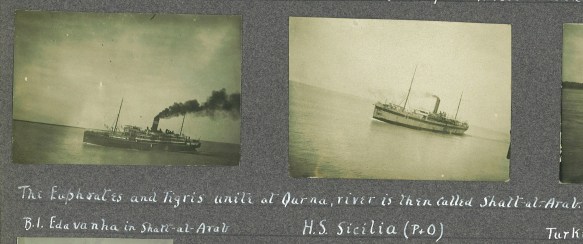

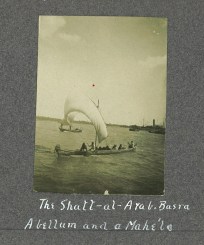

GTG records two ships in the Shatt-al-Arab, the famous waterway where the Euphrates and Tigris converge – the SS Edavanha owned by B.I. (stands for British India Steam Navigation Company, a well known shipping line at the time, actually owned by P&O) and the H.S. Sicilia (HS stands for Hospital Ship) owned by P&O (Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company) – GTG’s former employer.

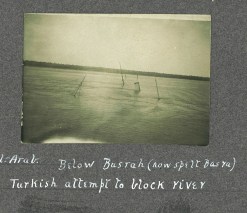

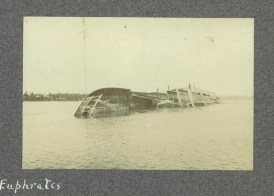

The photos also shows sunken vessels in the waterway – scuttled by the Turks in an attempt to prevent shipping:

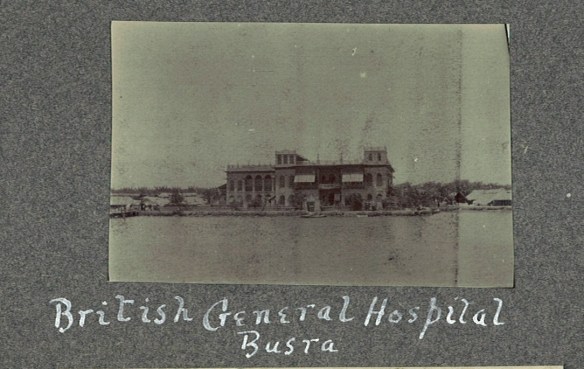

There are photos of the General Hospital at ‘Busra’ and a hospital ship aboard a ‘steernwheeler’ at Nasiriyeh

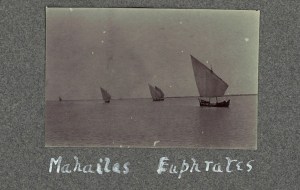

GTG also took photos of the smaller, local river craft, ‘bellums’ and ‘mahailas’ which are mentioned in the Battalion War Diary as used for carrying men and stores.

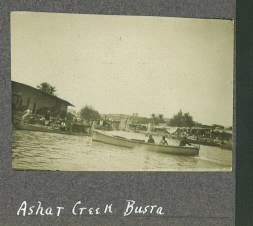

There are photos too of Ashar Creek and Margil in ‘Busra’, where the battalion had disembarked on 14 March 1916.

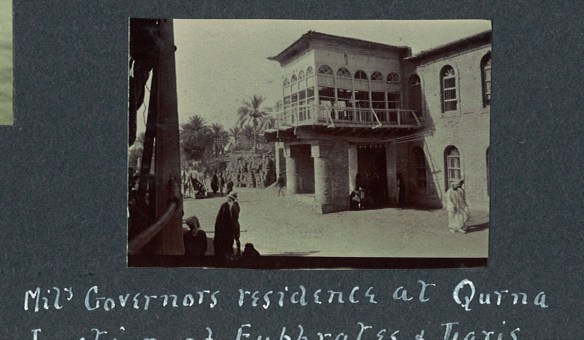

And the Military Governor’s House at Qurna.

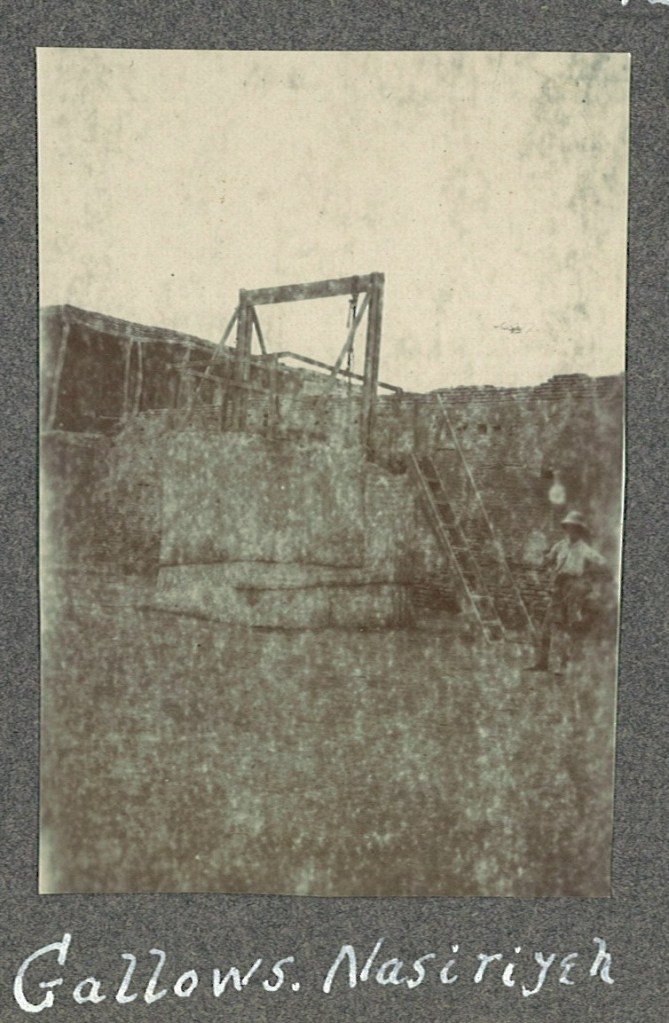

There is also a rather morbid photo of the gallows at Nasiriyeh:

Finally there are photos of the troops, engaged in building the defensive ‘bund’ against the flooding. The spring flooding of the rivers was particularly severe in April / May 1916.

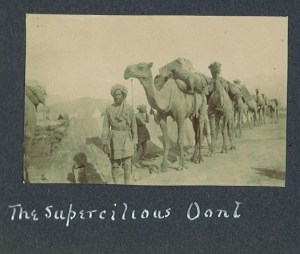

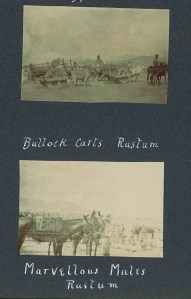

“The Supercilious Oont” ! – ‘oont’ was an Anglo-Indian word for a camel. It seems transportation was a problem and the carts had difficulties in the water-logged terrain. Camels were used as well as reliance on local water vessels such as the bellums and mahailas pictured above.

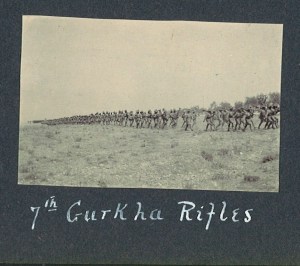

The above photo claims these are the 7th Gurkha Rifles but I’m not sure this is correct. 2/7GR were part of the forces besieged at Kut-al-Amra in early 1916 and then captured and imprisoned upon the surrender of Kut. I understand that 2/7GR was reformed in Mesopotamia in 1916 and this may be the reformed battalion. Or it may be a photo of 1/7GR back in India taken earlier before GTG left for Mesopotamia. Or it may be another Gurkha regiment, perhaps 5th Gurkha Rifles who were part of the same brigade as 2/6GR – the 42nd Indian Infantry Brigade in the 15th Indian Division.

It is not known how long GTG served in Mesopotamia but he is recorded as ‘Granted temporary rank of Captain whilst holding appointment as Platoon Commander at School of Instruction for Officers – 31st October 1917’

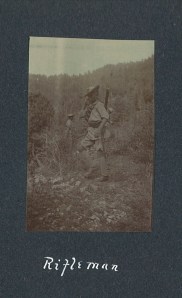

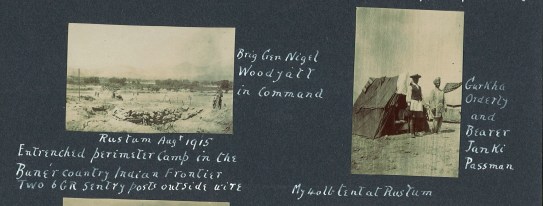

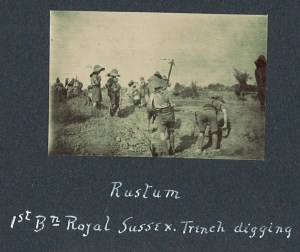

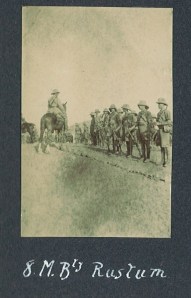

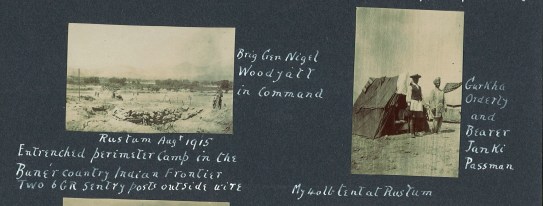

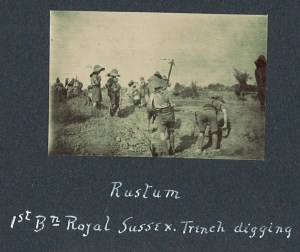

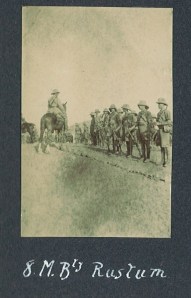

GTG on the North West Frontier 1915

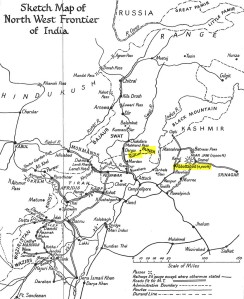

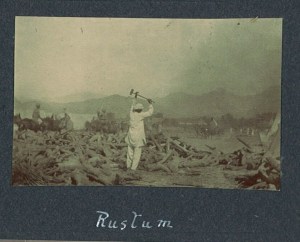

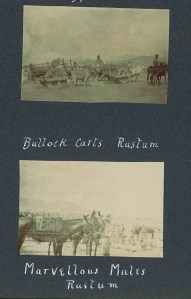

GTG was commissioned into the 2/6 Gurkha Rifles in March 1915 based at Abbotabad on the North West Frontier of India (now Pakistan)

In 1915, the 2/6th Gurkhas (2/6 GR) were part of the 3rd Infantry Brigade, in the 1st (Peshawar)

Division, defending the border of North West Frontier from attack by

various tribesmen including the Mohmands, the Bunerwals and the Swatis.

In August 1915 2/6 GR were sent to Rustam as part of a force to repulse

the Buner tribesmen.

The background and various engagements on the North West Frontier during 1915 are excellently described by F.A. MacKenzie in his chapter entitled ‘The Defence of India’ from ‘The Great War’, edited by H.W. Wilson & J.A. Hammerton, volume 7, chapter 128 :

“In the north-west trouble first came to a head in the Tochi Valley, in the strip of mountain land between British India and Afghanistan. It became evident towards the end of 1914 that great attempts were being made to stir up the frontier tribes, and to enlist them in a Jehad against the British.

…

For some months after this there was peace along this part of the frontier—an armed peace however, where the tribesmen were restrained by the sound common-sense of our civil authorities, and where a force of troops waited behind, ready to deal with trouble immediately it came to a head.

At the end of 1914 reports were received from different quarters of serious trouble brewing in the Mohmand country. The Mohmands are a powerful Pathan tribe, living partly in Afghanistan and partly in the districts around Peshawar. They are turbulent, fanatical, and quarrelsome; ready subjects for fiery Mullahs to stir up to revolt. Long before the outbreak of the war they had been in repeated conflicts with the British. Between 1872 and 1908 there had been several expeditions against them. In January, 1915, there came a raid in the neighbourhood of Shabkadar, a fortified post eighteen miles north of Peshawar, but it was easily driven off. In April it was reported that the Mohmands were collecting with a view to raiding Shabkadar. It was evident that a serious blow was now being planned, and the British forces in the district were greatly strengthened. The Khyber Movable Column was brought up and other troops held in readiness. On April 18th the tribesmen attempted to advance, but were met by our troops and driven back to the hills, where the British did not attempt to follow them.

After this repulse the trouble died down for a time, and some of the troops were temporarily withdrawn. But it was soon abundantly evident that the Mullahs did not mean to allow things to rest. All possible religious pressure was being brought on these Mohammedan tribes to make them fight again. There were large tribal gatherings in which fanatical preachers played on the feelings of the assembled hill- men and roused them to fury, painting in glowing colours the possibility of success, and promising Paradise to those who fell in the battle between the Crescent and the Cross. The Ramadan fast, in July, brought a temporary respite, but throughout the whole summer the British Movable Columns were kept constantly on the alert, and the troops had always to be ready to resist an advance. In August, Haji Sahib of Turangzai, a notorious anti-British Mullah, gathered several thousand men around him in the Ambela Pass, and prepared to invade British territory. The men he had assembled around him were not to be despised. The majority of them were Pathan hillmen, trained in fighting from boyhood. Scattered among them were a group of Hindu fanatics. Then there were fakirs of many kinds, reputed miracle workers, men of extraordinary austerity—fierce, lean, keen religionists, who showed the marks on their own bodies of the tortures they had delighted to inflict on themselves to prove the sincerity of their faith. Every factor that in previous generations had made the Mohammedans so tremendous a force in warfare in semi-civilised lands was embodied here. Each man was taught that Heaven itself would help him in the fight, that angels would come to strengthen his arm, and that Paradise was his.

…

On August 17th a hostile gathering of 3,000 or 4,000 tribesmen came down from the Ambela Pass towards Rustam. It was reported that another force was coming to support them. British troops at once pushed up to attack the Ambela Pass party before it was reinforced,’ and drove it back with great loss. The 91st Battery Royal Field Artillery came up during the course of the action after a forced march, its shells doing great execution. A brigade was now concentrated at this point, and wherever the tribesmen appeared it attacked them. In the latter part of August there were three fights between our troops and the tribesmen, and on each occasion the enemy was driven back into the hills, and the villages which had sheltered him were destroyed.

A still more formidable gathering of hillmen under a fakir, known as the Sandaki Mullah, advanced down the left bank of the Swat River to invade the Lower Swat. This force was reported to be between 17,000 and 20,000 strong. The Malakand Movable Column took up a position on the left bank of the river on a ridge known as the Landakai Ridge, which gave them a great advantage of position in meeting the hostile advance. The tribesmen attacked our outposts in strong force on the evening of August 28th and 29th, but were driven off. Next day the Malakand Column moved out, destroyed a fort, and shelled several villages held by the enemy. The tribesmen scattered, and for the time their offensive was broken The fanatics were at work on the Mohmand border, and the reports from here were so threatening that two brigades and a mobile column were ordered up to Shabkadar with a mounted column and divisional artillery, while a mobile column was formed at Mardan and subsequently moved to Abazai. Other troops were held in readiness to proceed to the Mohmand front if necessary.

There had been various large tribal gatherings in the Mohmand country, and early in September considerable numbers of the men moved down to the foot-hills and prepared sangars in the vicinity of Hafiz Kor. The movements of these tribesmen were carefully watched, but for the moment they were left alone, our aim being to permit them to come down from the mountains on to the plains where our troops could deal with them. The enemy grew in numbers until by the evening of September 4th they totalled fully 10,000. Then Major-General F. Campbell, commanding the British troops, determined to attack. The battle that followed was the biggest that had taken place on the North-West Frontier since 1897. Some of the British and Indian troops that took part in the engagement had reached their positions after record journeys. A British and Indian force covered a thirty-four mile march to Abazai, where the revolting tribes were reported in strong force, in ten marching hours, travelling at night and going over roads described by one officer who took part in the fight as “the most appalling I have ever seen.” The dust was two feet deep. “You can imagine what this was like with cavalry on ahead of us and all our transport. I shall never forget the march as long as I live, nor will the others, and added to the dust was the frightful stifling heat. Not a man fell out, which is an extraordinary performance, especially as the last nine miles from Zearn to Abazai were done in the hottest part of the day— 12 to 3 p.m.—arriving at Abazai, the hottest and most mosquito and sandfly-ridden place on the frontier. The weary soldiers were bitten all night.”

Those troops were then ordered on to Matta, a levy post on the Shabkadar-Abazai road, where our outposts had already been heavily engaged and had been driven in, Mohmands estimated at 3,000 strong having practically surrounded them.

The troops who were engaged in this fighting with the Mohmands and their neighbours included many notable corps — the famous 21st (Empress of India’s) Lancers, Skinner’s Horse, Lumsden’s Guides, Watson’s Horse, the 14th Lancers, the Liverpool Regiment, the Royal Sussex Regiment, the North Staffordshires, and the Durham Light Infantry, besides Punjabis, Rajputs, Gurkhas, the Guides, the Sikhs, and the Dogras. Nor must we forget the Royal Artillery, who did very notable work.

On the morning of September 5th the tribesmen, who had come down from the hills by the Kuhn Pass, advanced right in the open nearly down to the Shabkadar village. As they approached, the British howitzers and field-guns opened on them, but the tribesmen kept on, threatening our left. Thereupon two squadrons of the 21st Lancers, one squadron of the 14th Lancers, and one squadron of a mounted battery of the Royal Horse Artillery moved out to meet them. Our troops moved out around Shabkadar village and occupied some foot-hills to the north. The Mohmands, ignoring the Indian Cavalry, concentrated their fire upon the British Lancers. The gallant 21st were eager to distinguish themselves, for it was then within two days of the anniversary of their great charge at Omdurman in 1898. The Mohmands were entrenched in their sangars and in the nullahs (deep, dry ditches) along the foot of the hills. The 21st Lancers charged full against a large force, went through them, and turned straight again into a dense mass of Mohmands.

At one point they were charging over what they thought to be level ground when a blind nullah intervened. To quote the description of one soldier of the Royal Sussex Regiment: “The 21st Lancers charged what they thought to be a small belt, but came suddenly on a big ditch, and a lot of horses and men fell in. Then two I out of the grass on the other side about 3,000 Mohmands came. The only thing they could do was to charge. They went right through them, turned round, and charged back again. One chap, about nineteen years old, just out from England, killed five with his lance, leaving it sticking in the fifth one, and two more with his sword.” The British cavalry came out splendidly. Emerging from the bed of the Minchi-Abazai Canal they came under very heavy fire at close range. They charged the enemy a third time, and in this charge, which really decided the battle, they suffered heavily. Many stories of the fighting were afterwards told by the survivors. Lieut.-Colonel Scriven led his squadron in the charge, and did great execution with his sword until his horse was shot and fell upon him. Two of his lance-corporals assisted him to his feet. Shortly afterwards he was shot through the heart and fell, shouting, “Go on, lads. I’m done.” Two men guarded his body until they were rescued. Captain Anderson who had been severely wounded, fought desperately with his revolver until he was shot dead. Lieut. Thompson was so severely wounded that he died in the evening. Of five officers who rode in the charge three were killed and one wounded, the adjutant alone coming out unhurt. He, however, had his horse shot from under him, and was only fifty yards from the enemy when he was rescued by a shoeing-smith. One sergeant was unhorsed, and after killing two natives, grappled with a third huge native on the ground. Each man had his hand at the other’s throat, when another sergeant came up and shot the native. At the same moment he himself was shot and severely wounded.

All the troops engaged did well. The Sussex and the Staffordshires were engaged in fierce hand-to-hand fighting with the enemy. But it was undoubtedly the charges of the Lancers that saved the day. Their tremendous courage and irresistible elan cowed for the moment even the fanaticism of the Mohammedan tribesmen. After some hours of fighting the Mohmands broke and the cavalry pursued them to the hills.

Although the Mohmands and their neighbours were thus repulsed, they were still not wholly broken. The Mullahs made fresh efforts to stir them up, and early in October some 9,000 men again gathered in the neighbourhood of Hafiz Kor.

The British forces under Major-General Campbell, which had been strengthened by the addition of another brigade, took the offensive against them. The enemy fought well and offered strong opposition, but in the end was defeated. This occasion was especially notable because armoured cars were used for the first time in actual fighting in India, and proved of great value. They were exceedingly successful both in reconnaissance work and in covering some of the movements of our cavalry. This fight practically brought the unrest among the Mohmands to an end.

In October there was an outbreak in Swat, when 3,000 Bajauris advanced towards Chakdara to stir up the troops of Dir and Swat to attack the fort there. Lieut.-Colonel C. C. Luard, of the Durham Light Infantry, who was then temporarily in command of the Malakand Movable Column, decided to attack the enemy. He did so with the utmost vigour. He drove them back, pursued them, captured a standard, and gave them a lesson which evidently went right to their hearts, for months afterwards it was officially reported that there had been no further gathering of the tribes on that border.

There were some more minor troubles along the frontier, but little, if any, more than would have happened at ordinary times. In Baluchistan one chief looted the treasury of the Khan of Kalat, and it was feared that the trouble might spread, but a column visited the district, and things rapidly settled down. There was an attempt to raise a Jehad among the Black Mountain tribes in the summer of 1915, but it came to nothing. Peace was maintained on the British side of the border of the Shan States, but the French experienced some trouble on their side. Their post at Samenna was attacked and looted by a strong band of Chinese. Troops were hurried to the scene. The marauders were intercepted, and two hundred killed in action. Another band of considerable strength had also to be broken up. But these disturbances were really due not so much to the European War as to the fact that a large number of disbanded Chinese soldiers, with no money and no means of returning to their homes, had become brigands and were ready for any trouble.

It is difficult to convey to readers unacquainted with life in Northern India any idea of the great hardships gladly endured by the British troops in the frontier campaigns during the war. Young British soldiers found themselves exposed to great variations of climate, to tremendous heat, to nights of bitter cold, to shortage of supplies, and to physical efforts of the most exhausting type. Thrown into mountain country, pitted against tribesmen of magnificent physique, who were fighting on their own territory and accustomed to mountain war, with little public appreciation and with the knowledge that their own countrymen knew little of what they did, they fought their lonely fight with a magnificent endurance that was the admiration of all who knew of them. Some idea of the physical trials of our troops was obtained by the British public by the report of one ghastly journey of troops moving from Karachi to Peshawar in June, 1916. They had to travel through one of the hottest regions in India, where the shade temperature is constantly above 120 degrees. A large number of the men collapsed, and nineteen deaths were officially reported. In this case the great strain on the men was accentuated by amazing official neglect, a neglect for which three high officers Were subsequently dismissed from their posts. Such neglect was exceptional, but severities of heat and biting cold almost undreamed of in England were, time and again, the inevitable lot of the soldiers who so bravely kept the peace for Britain on the Indian Frontier.”

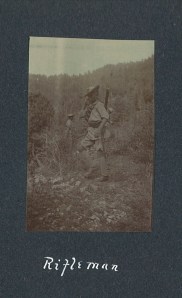

GTG

and men of 2/6GR in a ‘sangar’ – a small temporary fortified position

made up of stone, typical of the NW Frontier (nowadays built of sandbags

and still used in Afganistan)

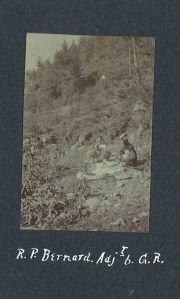

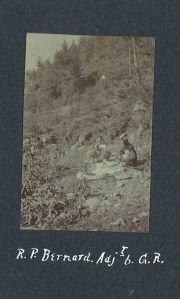

Capt. R.P.St.V. Bernard, M.C.

The background and various engagements on the North West Frontier during 1915 are excellently described by F.A. MacKenzie in his chapter entitled ‘The Defence of India’ from ‘The Great War’, edited by H.W. Wilson & J.A. Hammerton, volume 7, chapter 128 :

“In the north-west trouble first came to a head in the Tochi Valley, in the strip of mountain land between British India and Afghanistan. It became evident towards the end of 1914 that great attempts were being made to stir up the frontier tribes, and to enlist them in a Jehad against the British.

…

For some months after this there was peace along this part of the frontier—an armed peace however, where the tribesmen were restrained by the sound common-sense of our civil authorities, and where a force of troops waited behind, ready to deal with trouble immediately it came to a head.

At the end of 1914 reports were received from different quarters of serious trouble brewing in the Mohmand country. The Mohmands are a powerful Pathan tribe, living partly in Afghanistan and partly in the districts around Peshawar. They are turbulent, fanatical, and quarrelsome; ready subjects for fiery Mullahs to stir up to revolt. Long before the outbreak of the war they had been in repeated conflicts with the British. Between 1872 and 1908 there had been several expeditions against them. In January, 1915, there came a raid in the neighbourhood of Shabkadar, a fortified post eighteen miles north of Peshawar, but it was easily driven off. In April it was reported that the Mohmands were collecting with a view to raiding Shabkadar. It was evident that a serious blow was now being planned, and the British forces in the district were greatly strengthened. The Khyber Movable Column was brought up and other troops held in readiness. On April 18th the tribesmen attempted to advance, but were met by our troops and driven back to the hills, where the British did not attempt to follow them.

After this repulse the trouble died down for a time, and some of the troops were temporarily withdrawn. But it was soon abundantly evident that the Mullahs did not mean to allow things to rest. All possible religious pressure was being brought on these Mohammedan tribes to make them fight again. There were large tribal gatherings in which fanatical preachers played on the feelings of the assembled hill- men and roused them to fury, painting in glowing colours the possibility of success, and promising Paradise to those who fell in the battle between the Crescent and the Cross. The Ramadan fast, in July, brought a temporary respite, but throughout the whole summer the British Movable Columns were kept constantly on the alert, and the troops had always to be ready to resist an advance. In August, Haji Sahib of Turangzai, a notorious anti-British Mullah, gathered several thousand men around him in the Ambela Pass, and prepared to invade British territory. The men he had assembled around him were not to be despised. The majority of them were Pathan hillmen, trained in fighting from boyhood. Scattered among them were a group of Hindu fanatics. Then there were fakirs of many kinds, reputed miracle workers, men of extraordinary austerity—fierce, lean, keen religionists, who showed the marks on their own bodies of the tortures they had delighted to inflict on themselves to prove the sincerity of their faith. Every factor that in previous generations had made the Mohammedans so tremendous a force in warfare in semi-civilised lands was embodied here. Each man was taught that Heaven itself would help him in the fight, that angels would come to strengthen his arm, and that Paradise was his.

…

On August 17th a hostile gathering of 3,000 or 4,000 tribesmen came down from the Ambela Pass towards Rustam. It was reported that another force was coming to support them. British troops at once pushed up to attack the Ambela Pass party before it was reinforced,’ and drove it back with great loss. The 91st Battery Royal Field Artillery came up during the course of the action after a forced march, its shells doing great execution. A brigade was now concentrated at this point, and wherever the tribesmen appeared it attacked them. In the latter part of August there were three fights between our troops and the tribesmen, and on each occasion the enemy was driven back into the hills, and the villages which had sheltered him were destroyed.

A still more formidable gathering of hillmen under a fakir, known as the Sandaki Mullah, advanced down the left bank of the Swat River to invade the Lower Swat. This force was reported to be between 17,000 and 20,000 strong. The Malakand Movable Column took up a position on the left bank of the river on a ridge known as the Landakai Ridge, which gave them a great advantage of position in meeting the hostile advance. The tribesmen attacked our outposts in strong force on the evening of August 28th and 29th, but were driven off. Next day the Malakand Column moved out, destroyed a fort, and shelled several villages held by the enemy. The tribesmen scattered, and for the time their offensive was broken The fanatics were at work on the Mohmand border, and the reports from here were so threatening that two brigades and a mobile column were ordered up to Shabkadar with a mounted column and divisional artillery, while a mobile column was formed at Mardan and subsequently moved to Abazai. Other troops were held in readiness to proceed to the Mohmand front if necessary.

There had been various large tribal gatherings in the Mohmand country, and early in September considerable numbers of the men moved down to the foot-hills and prepared sangars in the vicinity of Hafiz Kor. The movements of these tribesmen were carefully watched, but for the moment they were left alone, our aim being to permit them to come down from the mountains on to the plains where our troops could deal with them. The enemy grew in numbers until by the evening of September 4th they totalled fully 10,000. Then Major-General F. Campbell, commanding the British troops, determined to attack. The battle that followed was the biggest that had taken place on the North-West Frontier since 1897. Some of the British and Indian troops that took part in the engagement had reached their positions after record journeys. A British and Indian force covered a thirty-four mile march to Abazai, where the revolting tribes were reported in strong force, in ten marching hours, travelling at night and going over roads described by one officer who took part in the fight as “the most appalling I have ever seen.” The dust was two feet deep. “You can imagine what this was like with cavalry on ahead of us and all our transport. I shall never forget the march as long as I live, nor will the others, and added to the dust was the frightful stifling heat. Not a man fell out, which is an extraordinary performance, especially as the last nine miles from Zearn to Abazai were done in the hottest part of the day— 12 to 3 p.m.—arriving at Abazai, the hottest and most mosquito and sandfly-ridden place on the frontier. The weary soldiers were bitten all night.”

Those troops were then ordered on to Matta, a levy post on the Shabkadar-Abazai road, where our outposts had already been heavily engaged and had been driven in, Mohmands estimated at 3,000 strong having practically surrounded them.

The troops who were engaged in this fighting with the Mohmands and their neighbours included many notable corps — the famous 21st (Empress of India’s) Lancers, Skinner’s Horse, Lumsden’s Guides, Watson’s Horse, the 14th Lancers, the Liverpool Regiment, the Royal Sussex Regiment, the North Staffordshires, and the Durham Light Infantry, besides Punjabis, Rajputs, Gurkhas, the Guides, the Sikhs, and the Dogras. Nor must we forget the Royal Artillery, who did very notable work.

On the morning of September 5th the tribesmen, who had come down from the hills by the Kuhn Pass, advanced right in the open nearly down to the Shabkadar village. As they approached, the British howitzers and field-guns opened on them, but the tribesmen kept on, threatening our left. Thereupon two squadrons of the 21st Lancers, one squadron of the 14th Lancers, and one squadron of a mounted battery of the Royal Horse Artillery moved out to meet them. Our troops moved out around Shabkadar village and occupied some foot-hills to the north. The Mohmands, ignoring the Indian Cavalry, concentrated their fire upon the British Lancers. The gallant 21st were eager to distinguish themselves, for it was then within two days of the anniversary of their great charge at Omdurman in 1898. The Mohmands were entrenched in their sangars and in the nullahs (deep, dry ditches) along the foot of the hills. The 21st Lancers charged full against a large force, went through them, and turned straight again into a dense mass of Mohmands.

At one point they were charging over what they thought to be level ground when a blind nullah intervened. To quote the description of one soldier of the Royal Sussex Regiment: “The 21st Lancers charged what they thought to be a small belt, but came suddenly on a big ditch, and a lot of horses and men fell in. Then two I out of the grass on the other side about 3,000 Mohmands came. The only thing they could do was to charge. They went right through them, turned round, and charged back again. One chap, about nineteen years old, just out from England, killed five with his lance, leaving it sticking in the fifth one, and two more with his sword.” The British cavalry came out splendidly. Emerging from the bed of the Minchi-Abazai Canal they came under very heavy fire at close range. They charged the enemy a third time, and in this charge, which really decided the battle, they suffered heavily. Many stories of the fighting were afterwards told by the survivors. Lieut.-Colonel Scriven led his squadron in the charge, and did great execution with his sword until his horse was shot and fell upon him. Two of his lance-corporals assisted him to his feet. Shortly afterwards he was shot through the heart and fell, shouting, “Go on, lads. I’m done.” Two men guarded his body until they were rescued. Captain Anderson who had been severely wounded, fought desperately with his revolver until he was shot dead. Lieut. Thompson was so severely wounded that he died in the evening. Of five officers who rode in the charge three were killed and one wounded, the adjutant alone coming out unhurt. He, however, had his horse shot from under him, and was only fifty yards from the enemy when he was rescued by a shoeing-smith. One sergeant was unhorsed, and after killing two natives, grappled with a third huge native on the ground. Each man had his hand at the other’s throat, when another sergeant came up and shot the native. At the same moment he himself was shot and severely wounded.

All the troops engaged did well. The Sussex and the Staffordshires were engaged in fierce hand-to-hand fighting with the enemy. But it was undoubtedly the charges of the Lancers that saved the day. Their tremendous courage and irresistible elan cowed for the moment even the fanaticism of the Mohammedan tribesmen. After some hours of fighting the Mohmands broke and the cavalry pursued them to the hills.

Although the Mohmands and their neighbours were thus repulsed, they were still not wholly broken. The Mullahs made fresh efforts to stir them up, and early in October some 9,000 men again gathered in the neighbourhood of Hafiz Kor.

The British forces under Major-General Campbell, which had been strengthened by the addition of another brigade, took the offensive against them. The enemy fought well and offered strong opposition, but in the end was defeated. This occasion was especially notable because armoured cars were used for the first time in actual fighting in India, and proved of great value. They were exceedingly successful both in reconnaissance work and in covering some of the movements of our cavalry. This fight practically brought the unrest among the Mohmands to an end.

In October there was an outbreak in Swat, when 3,000 Bajauris advanced towards Chakdara to stir up the troops of Dir and Swat to attack the fort there. Lieut.-Colonel C. C. Luard, of the Durham Light Infantry, who was then temporarily in command of the Malakand Movable Column, decided to attack the enemy. He did so with the utmost vigour. He drove them back, pursued them, captured a standard, and gave them a lesson which evidently went right to their hearts, for months afterwards it was officially reported that there had been no further gathering of the tribes on that border.

There were some more minor troubles along the frontier, but little, if any, more than would have happened at ordinary times. In Baluchistan one chief looted the treasury of the Khan of Kalat, and it was feared that the trouble might spread, but a column visited the district, and things rapidly settled down. There was an attempt to raise a Jehad among the Black Mountain tribes in the summer of 1915, but it came to nothing. Peace was maintained on the British side of the border of the Shan States, but the French experienced some trouble on their side. Their post at Samenna was attacked and looted by a strong band of Chinese. Troops were hurried to the scene. The marauders were intercepted, and two hundred killed in action. Another band of considerable strength had also to be broken up. But these disturbances were really due not so much to the European War as to the fact that a large number of disbanded Chinese soldiers, with no money and no means of returning to their homes, had become brigands and were ready for any trouble.

It is difficult to convey to readers unacquainted with life in Northern India any idea of the great hardships gladly endured by the British troops in the frontier campaigns during the war. Young British soldiers found themselves exposed to great variations of climate, to tremendous heat, to nights of bitter cold, to shortage of supplies, and to physical efforts of the most exhausting type. Thrown into mountain country, pitted against tribesmen of magnificent physique, who were fighting on their own territory and accustomed to mountain war, with little public appreciation and with the knowledge that their own countrymen knew little of what they did, they fought their lonely fight with a magnificent endurance that was the admiration of all who knew of them. Some idea of the physical trials of our troops was obtained by the British public by the report of one ghastly journey of troops moving from Karachi to Peshawar in June, 1916. They had to travel through one of the hottest regions in India, where the shade temperature is constantly above 120 degrees. A large number of the men collapsed, and nineteen deaths were officially reported. In this case the great strain on the men was accentuated by amazing official neglect, a neglect for which three high officers Were subsequently dismissed from their posts. Such neglect was exceptional, but severities of heat and biting cold almost undreamed of in England were, time and again, the inevitable lot of the soldiers who so bravely kept the peace for Britain on the Indian Frontier.”

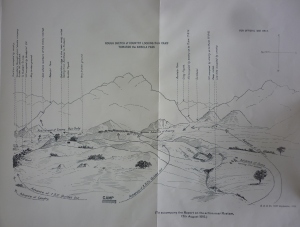

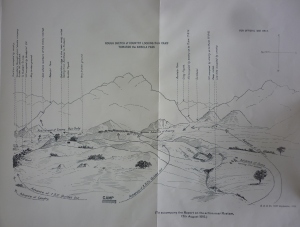

The actions at Rustam are recorded in more detail in the official

report by Major-General F Campbell. I have illustrated the following

extract with a sketch map from an earlier official report and GTG’s own

photos of the action at Rustam:

.

“Report from Major General F. Campbell, C.B., D.S.O., General Officer Commanding, 1st (Peshawar) Division on the Operations on the Swat, Buner and Mohmand Borders, 19th June – 25th October, 1915.

General Staff India – Case no. 13035 – 1915 [National Archives: WO 100/732]

Dated Peshawar, the 26th October 1915.

From – Major General F. Campbell, C.B., D.S.O., Commanding 1st (Peshawar) Division,

To – The Chief of the General Staff, Army Headquarters, Delhi.

I have the honour to submit the following report on the operations of the Swat, Buner and Mohmand Borders between the 19th June to the 27th October 1915 :-

7. Consequently on the same date, (15th), I issued the following orders :-

I then ordered the reminder* of the 3rd Infantry Brigade (less the 2-1st Gurkha Rifles**), No. 8 Mountain Battery from Peshawar and one squadron 13th Lancers from Risalpur to concentrate at Rustam under Brigadier-General N.G. Woodyatt, Commanding 3rd Infantry Brigade.

9. The remainder of the 3rdInfantry Brigade and attached troops, with the exception of No.8 Mountain Battery and the section Sappers and Miners, were concentrated at Rustam by the morning of the 19th August. The Mountain Battery and section of Sappers and Miners arrived there on the 21st.

10. The camp was sniped nightly, resulting in one transport driver being killed and three sowars and one follower wounded : five horses and two mules were also wounded.

On the 21st August Brigadier Woodyatt took his brigade out towards the Pirsai pass, as the snipers appeared to come from that direction. Some 300 tribesmen were discovered, but got away before they could be dealt with. The brigade was then directed on Baringan village in the Malandri pass, where some parties of the enemy were engaged and losses to the extent of 12 killed and wounded inflicted. After this General Woodyatt was obliged to withdraw to his camp, owing to the prostration of the troops due to the intense heat.